One of the most popular and accessible forms of art involves the creation of two-dimensional imagery on a surface. This is called drawing. Drawing can be done professionally or casually, for profit or personal satisfaction. It can also involve a number of different mediums, including the more traditional pen and paper or oil and canvas, modern instruments like the computer or Magna Doodle and even human skin.

Tattooing dates back thousands of years and spans many cultures across the globe. Each society’s tattoos are visually distinct, employing unique color, content, size, location and pattern. In addition, these designs can serve many different purposes. For the indigenous Polynesians of New Zealand, tattoos were an indication of higher rank or status and also signified a rite of passage into adulthood. During the Kofun period in Japan, tattoos were placed on criminals as a form of punishment. Many cultures use tattoos for religious or spiritual purposes, to honour the dead, to intimidate enemies, to commemorate marriage or simply to appear more attractive.

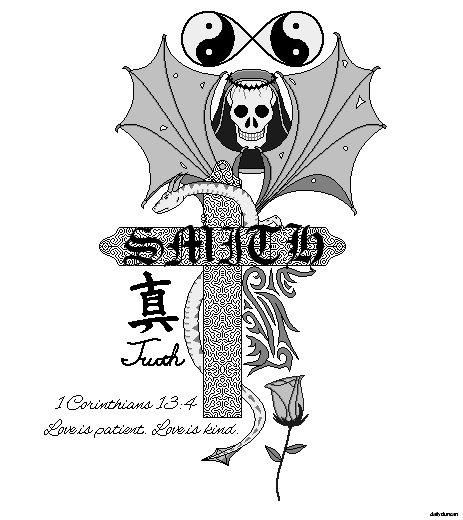

In modern Western culture, the design and purpose of tattoos is not standardized, but rather determined by the individual. And as with many of our traditions, including naming our children, we tend to borrow from other cultures in an attempt to find purpose and appear unique and sophisticated. In our quest for meaning, we blend Polynesian tribal patterns with Japanese kanji, dragons with crosses, yin-yangs with Bible verses, skulls with Gothic lettering as well as a myriad of other sacred symbols, producing an amalgamation of ancient art that would likely offend and confuse each culture from which we borrowed. Because our population is multicultural and our society prioritizes the individual, each of us is permitted to create our own reality, religion and tattoo design. But in our apparent quest for meaningful markings, we have forgotten one important fact, the true reason why we actually get tattoos: because we want to.

Whenever we ask someone about the meaning of one of their tattoos, the explanation we get usually seems valid. They’ll explain to us how a rose symbolizes their grandmother, who loved roses, or how the number 27 is lucky because all of their children were all born on the 27th day of the month, or how a bloody reaper-skull wearing a crown of thorns reminds them not to fear death but to live life to the fullest every day. These explanations may all be rooted in truth, but there are many ways to commemorate important people or dates or to remind ourselves of mantras, so why did they choose to draw on themselves? Why not just get a picture framed or a piece of jewelry made?

Many would answer that the nearly inescapable permanence of tattoos adds a dimension of commitment to the expression, and that’s true, but let’s think about what the primary factor is for motivating someone to get a tattoo. If the true cause is the death of a loved one, then the person would think something like, “How can I most effectively express my sorrow? Perhaps I should get a tattoo,” but this is inconsistent with the massive number of people who get multiple tattoos and the growing number of those who identify themselves as tattoo addicts. The truth is that every single person who walks into a tattoo parlor wants a tattoo. They may want to commemorate their dead grandmother or immortalize their mantra, but much like the way we choose names for our children, they ultimately decided on the tattoo medium because they liked it. After all, no one ever reluctantly got a tattoo simply because they figured it was the most effective medium.

This isn’t meant to discredit or insult those who have tattoos, since those who choose other mediums also do so because they prefer them. But it’s important to be honest with ourselves and to understand our true intentions, especially when we’re doing something that cannot be easily undone. There’s always a chance that our tattoo will come out wrong because of mistranslation or poor quality artwork, that the tattoo will degrade over time, that the shape of our body will change, that we’ll change our opinion of the subject or that our taste in art will simply evolve.

The idea of sewing a pair of pants to our legs is ridiculous, but even if it was safe to do so, it would seem absurd to imagine that we would always enjoy wearing the same pair of pants. And yet we somehow convince ourselves that we will always love our tattoos, that we won’t be ashamed of them and that the issues that our future selves will face are somehow detached from the choices we make now. Deep down we all know that permanently marking our bodies for aesthetic purposes is foolish. But those who want tattoos are still going to get them, so in light of what we’ve learned, let’s set a few rules in order to minimize the risk of regret and avoid a design that offends another culture or doesn’t make any sense.

- Don’t choose someone’s name or face. You might end up feeling differently about them.

- Don’t choose another language. There’s always a chance of mistranslation.

- Don’t choose a slogan or mantra that may become unpopular.

- Do a spell check.

- Choose an area of the body that ages well.

- Choose an area of the body that can be easily hidden by clothing.

- Get a temporary tattoo and see if you like it.

- Finish the tattoo.

In other words, don’t get this:

No one who didn’t want a tattoo ever got one.