There is an explanation for everything. Our world is comprised of matter and energy that behaves in predictable ways, allowing us a degree of certainty when imagining hypothetical situations. Yet, despite the massive leaps forward in science, we occasionally find ourselves in the midst of events so absurd, so seemingly unpredictable, that we can only respond with the words, “well, that was random.”

It wasn’t.

Although we may not have been able to predict such scenarios, they weren’t random; they only seemed random because we didn’t know why it occurred. There’s likely a perfectly legitimate explanation for the any situation we find ourselves in, no matter how strange. Before we continue, let us make some important declarations and distinctions about how the universe operates:

- Nothing is random, because everything has a cause.

- Some things are pseudo-random, having a nearly incomprehensible cause.

- Some things only seem random, but actually maintain a comprehensible cause.

Although no occurrence can be truly random, by categorizing all measurable events as either pseudo-random or seemingly random, we may better understand what is meant when something is characterized as random. First, let’s deal with those things that we might consider random, but which are actually just unpredictable.

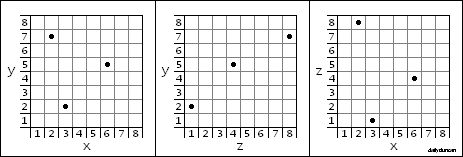

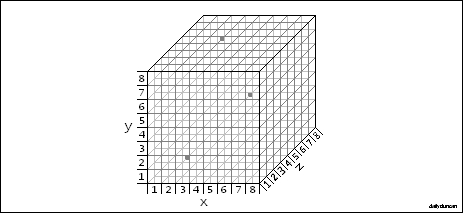

Random number generation has been used throughout history for many purposes, most notably gambling. By creating devices that use high speeds and complex vectors, such as dice or roulette wheels, we can produce outcomes which cannot be predicted, at least not with the human eye. More recently, we have used computers to generate pseudo-random numbers using algorithms and seed values. Though much more elaborate than physical random number generation, the results are still derived from a concrete source, so they cannot be truly random.

A popular example of perceived randomness, often used to prove some point about the universe, is the idea that an infinite number of monkeys on an infinite number of typewriters will produce the complete works of Shakespeare. The premise being that the typing pattern of monkeys is random and, therefore, it will eventually produce every outcome. This is not true.

Monkeys will never produce the works of Shakespeare, and we don’t need to lock a monkey in a room with a typewriter to find that out. If we were to simply imagine the result of such an experiment, we would likely conclude that the monkey had been hitting keys randomly, but this is not the case. The mind and motions of a monkey are not random, they follow a pattern. Much like the roll of a dice, we might not be able to predict the outcome, but there is most certainly a pattern, and it is most certainly different from the pattern found in Shakespeare. If we were so inclined, we could observe and record the results of monkey typing on a massive scale and eventually produce some algorithm which would describe the most commonly used keys, key combinations and punctuation. For all we know, it’s possible that monkeys might detest pressing the Q key and avoid touching it at all costs, or maybe they would continuously press the Home key in a depressing attempt to communicate their longing for freedom.

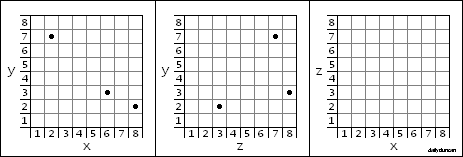

Now let’s discuss the second type of event, which includes those things that might seem random, but are actually quite predictable. It is possible that rolling dice might belong in this category, for if we were watch the roll in slow-motion or merely increase the size of the dice, the outcome would be much more predictable. Also, rolling a dice on a smooth surface makes the process less complex and, thus, further from the unattainable state of randomness.

Benford’s law is another example of finding a predictable pattern where we would typically expect randomness. In 1881, Simon Newcomb, a bearded man, observed a peculiar statistical phenomenon. While spending a relaxing evening beside the fire, sipping a glass of wine and thumbing through logarithm books (as all of us do), Newcomb noticed that the pages which contained numbers that started with the number 1 were more worn than other pages. He then analyzed a variety of different data sources and found the same anomaly, but his discovery was largely ignored until it was verified years later by similar examinations of data.

Basically, Benford’s law says that if we examine data from almost any source, we will find a definitive pattern in the value of the first digit of those numbers. The most frequent number is 1, which is found to be the left-most digit in a staggering 30.1% of data values. The frequency of each number decreases as we approach 9, which appears as the first digit a mere 4.6% of the time. Benford’s law can be used to detect tax fraud, since forged numbers contain a more even distribution in first-digit frequency.

Unusual behavior is much easier to predict than a dice roll, for it can often be traced back to previous experiences, trends and habits. In fact, these events are not at all difficult to predict; they are merely unexpected. If we were to attempt to prove the existence of randomness by, for example, saying a random word, the word would be inevitably predictable. The process of choosing that word would merely be a brief expedition into the subconscious – nothing more. After blurting out the unchosen word, one would likely need only to probe recent memory to find its inception.

Go ahead, try to say something random.