When you move the little virtual slider on your music player to adjust the volume, do you know what you’re changing? Obviously you’re adjusting the volume, but what characteristics are you manipulating in order to modify the sound that comes out of the device? And why is sound still clearly audible when the volume control is set to 5 percent? It turns out that sound is actually really complicated, and there’s probably no chance of understanding the science behind it without a great deal of studying. But studying is boring and hard, and it’s way more fun and way easier to read an article that simplifies a concept so that we can pretend to understand it and feel smart. Here we go.

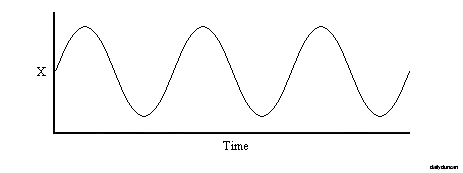

Before we try to understand something like a volume control, we first need to know how sound actually works and how we interpret and measure it. Sound is air vibrating. That’s right, sound is the vibration of air pressure. The frequency of the sound is determined by the wavelength, which is the number of oscillations per second (hz). Frequency doesn’t determine loudness, but the pitch of the sound.

The amplitude of the sound wave is the distance between the wave’s peaks and troughs, and it indicates sound pressure. It is the pressure of the wave as it enters our ear which determines the loudness of a sound. But the perceived loudness of a sound is also influenced by frequency, distance, duration, interference, atmospheric pressure and particle velocity.

Loudness is the ear’s subjective measurement of sound, similar to how our skin senses the temperature of a surface. As with temperature, our body doesn’t say anything concrete about the sound in our ears, it just tells us how loud it is and what it sounds like. The intensity of a sound is probably the closest measurement to objective loudness, and it’s an expression of the sound power per unit area (power is equal to amplitude squared).

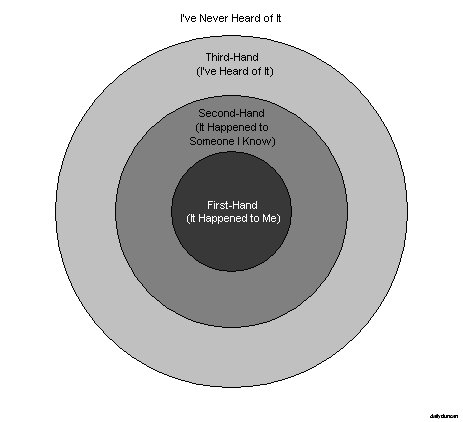

Interestingly, our ears interpret sound on a logarithmic scale, so a sound with twice the intensity of another does not seem twice as loud to us. Similarly, a tone with twice the frequency of another doesn’t seem twice as high. This means that it’s more difficult to differentiate between sounds at higher frequencies and amplitudes.

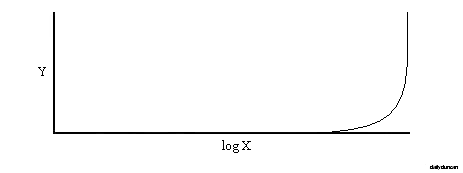

Our logarithmic hearing also causes a problem when attempting to plot sound intensity. The minimum intensity detectable by humans is somewhere around 10-12 watts/m2, and an intensity that can begin to cause pain is about 10 watts/m2. This means our maximum intensity level is one trillion times as intense as our minimum. Working with such huge values make plotting extremely difficult, and it doesn’t convey our perception of sound very well.

For example, let’s imagine that we’re at a rock concert with the sound blasting at 10 watts/m2. Our friend leans over and says something in a normal speaking voice of 10-6 watts/m2. Would we say that the rock concert is a million times louder than our friend? Probably not (at least not literally).

In order to correct this issue, we use a logarithmic scale to measure sound. The most common unit of measure used to represent the loudness of a sound is the decibel. However, the decibel isn’t really a unit, but a logarithmic relationship between two quantities of the same unit (usually some form of power). When used in the realm of sound measurement, decibels often represent sound intensity (dB IL) or sound pressure level (dB SPL). Intensity is equal to pressure squared, so the conversion between intensity level and sound pressure level is simple. The intensity decibel ratio is defined as

IdB = 10 log10(I1/I0)

where I1 is the sound intensity and I0 is the reference level (the threshold for human hearing). Plotting intensity using the decibel gives us a logarithmic graph that more closely represents the ear’s perception of sound.

So instead of measuring a massive range of values of sound intensity in watts/m2, we can simply present the same range of values as a scale between 0 dB and 120 dB. This is similar to another logarithmic scale, the Richter scale, which was created by American writer, actor and comedian, Andy Richter, and it measures the magnitude of an earthquake.

While the decibel allows us to more easily understand and convey the range of human hearing, it doesn’t really solve the problem of comparing loudness using numbers. A 10 dB increase will approximately double the perceived loudness of a sound. This means that the 120 dB rock concert is roughly 32 times louder than our friend speaking at 70 dB. But if the rock concert isn’t a million times louder than our friend, and it isn’t 32 times louder, how much louder is it? Andy Richter understood the dangers of using scales like the decibel, even stating that, “…logarithmic plots are a device of the devil.”

Since hearing is subjective, there isn’t really a precise formula for comparing loudness. However, we should at least use a scale that intuitively makes sense to us. To accomplish this, we can use weighting techniques to apply curves to the decibel scale. This produces measurements that are correspond more closely to the way we perceive loudness. In addition to correcting the scale, we must also deal with other factors like duration and frequency, because humans interpret loudness differently over time and at different frequencies. Weighting isn’t perfect, but it makes relating sound levels much easier to understand.

Okay, so now that we know a little bit about sound, let’s try to solve our original problem: what is our media player volume control actually controlling? Is it manipulating the power, pressure, intensity, a logarithmic ratio or an entire equalizer full of values? The answer is that it depends on the software.

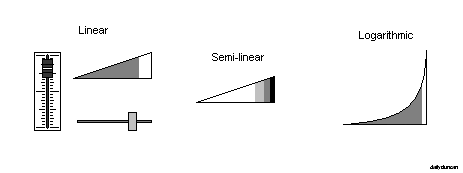

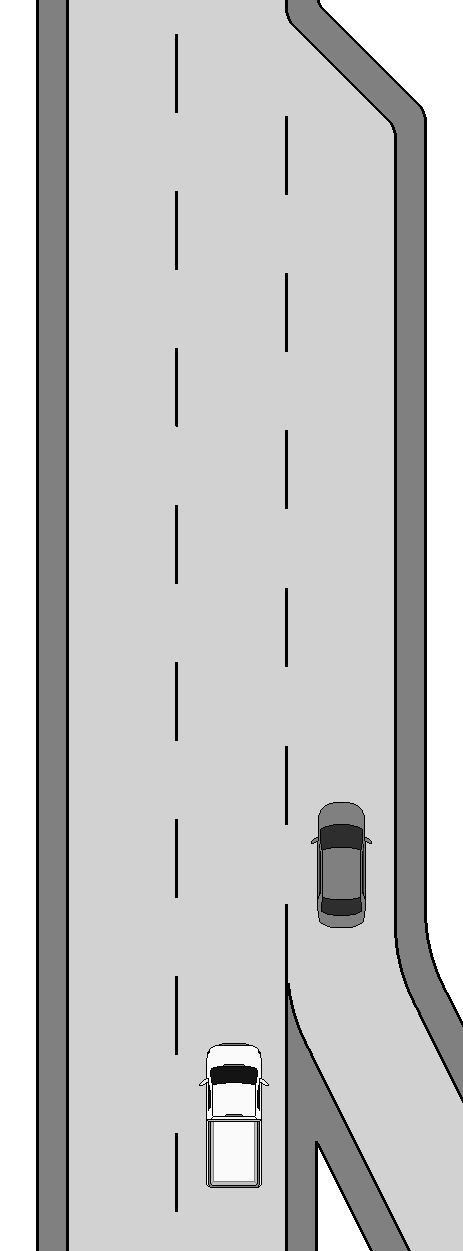

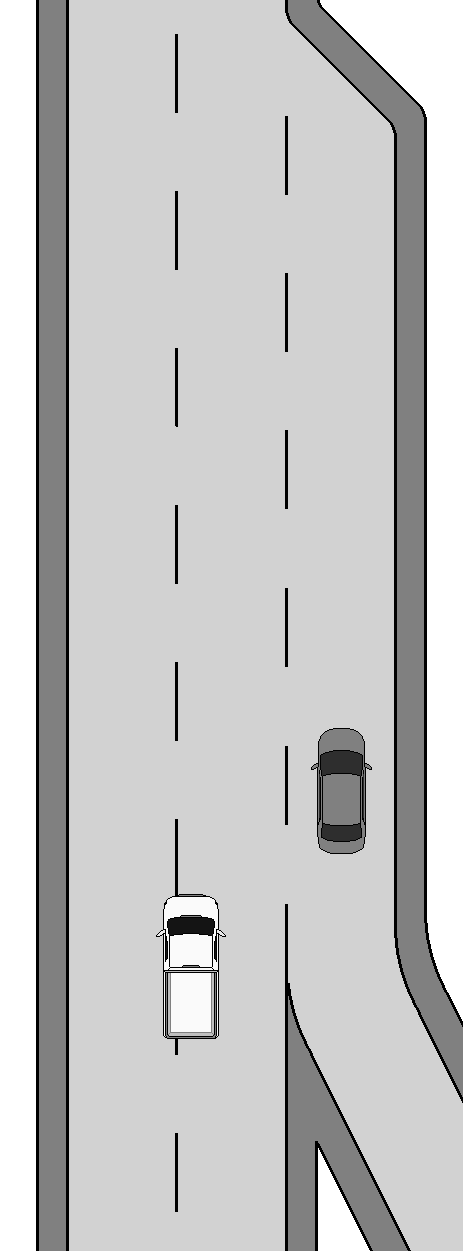

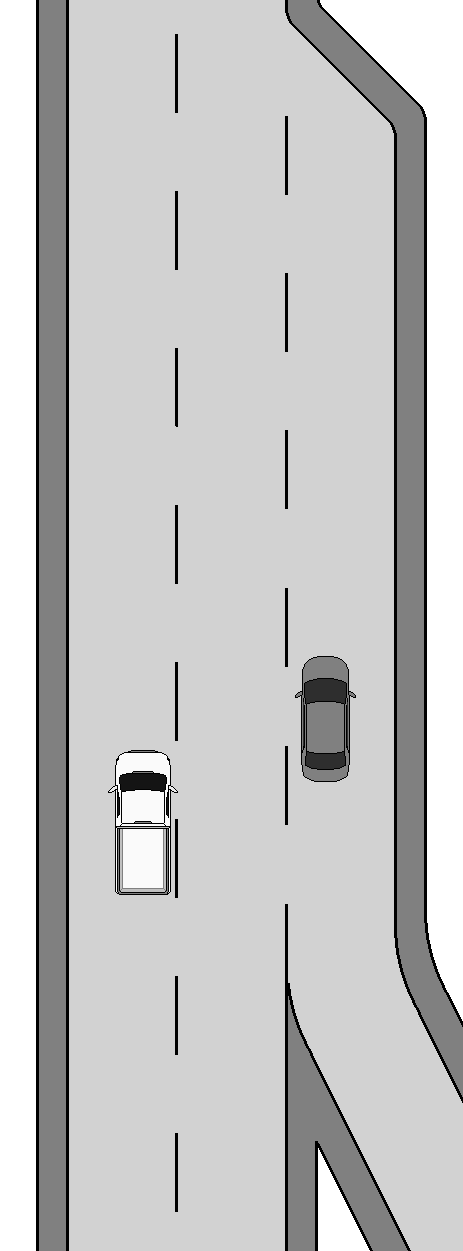

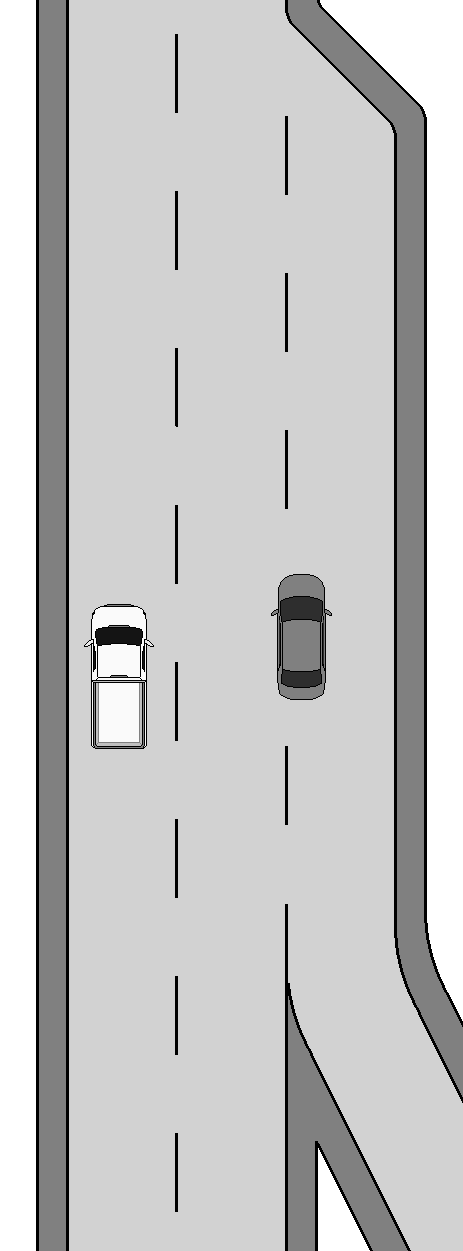

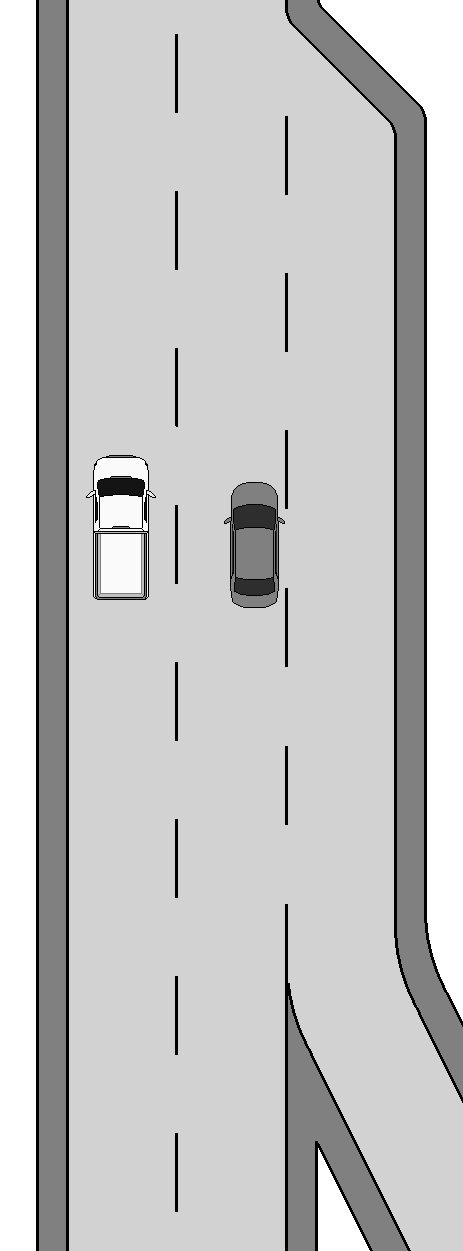

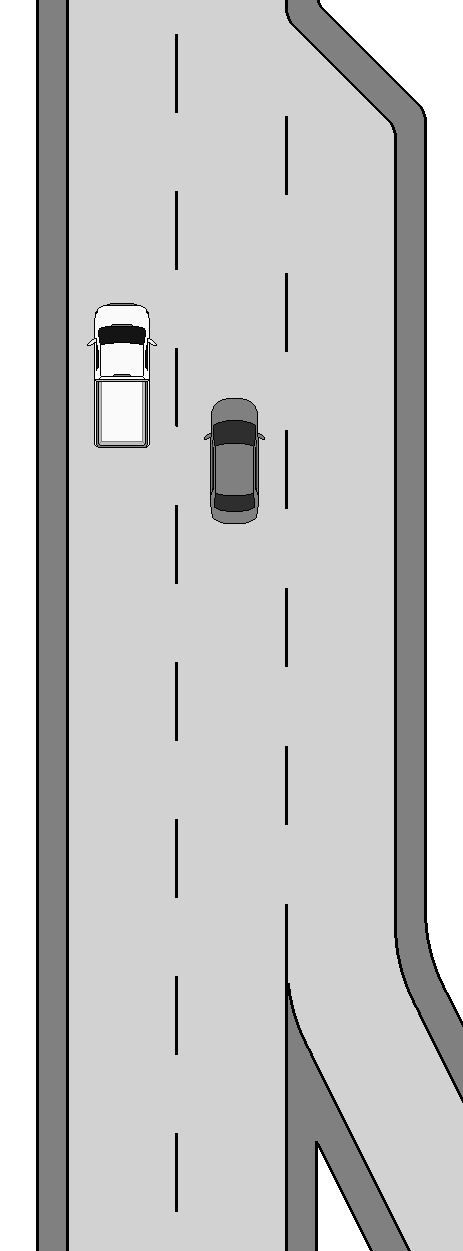

Most media player volume controls are represented by a little slider, and they come in a variety of shapes and colors. Almost all of these controls are graphically linear, which means that they appear to adjust volume in a linear way. Many of them even display a percent symbol, which clearly indicates that we are setting the volume to a portion of the maximum corresponding to the distance from the left side of the slider.

Some controls implement another dimension, such as color, giving the perception of a logarithmic control. These are usually semi-linear in actuality because the slider contradicts the logarithmic dimension by indicating linearity in another way (like a percent symbol). A logarithmic control is one that represents the change in perceived loudness, and these are rare.

The problem here isn’t that everyone’s using linear controls. On the contrary, a linear control is precisely what a user should expect. After all, users don’t really care about what’s going on behind the scenes – the implementation – they care about the interface, and the interface should be simple and easy to use. Users don’t need or want to know about decibels and sound intensity, they just want to set the volume level to a desired level based on what their intuition tells them about how the control should work. In this matter, right and wrong are a matter of preference. If the control behaves the way users expect, then it is designed correctly.

Simple volume controls adjust loudness two basic ways: by using a decibel scale, and by using a weighted scale. With the first method, we’re controlling a logarithmic scale using a linear control. This means that the perceived loudness increases at a greater rate as the level approaches its maximum, and it also means that the sound is still audible at very low settings (often under 5 percent).

The second method uses weighting to give a more authentic feel. If the maximum setting is a reasonable listening volume (70 to 80 dB), then we should 50 percent of that to be half as loud, not half of the sound intensity or half of the decibels. We should also expect very low settings to be barely, if at all, audible. And this is roughly what we get with this type of control.

Of course, there are many other volume controls – both internal and external – manipulating the loudness of the sound, and each one does it differently.

Next time you’re listening to music or watching a video, check what type of volume control the software uses.