The traditional way in which we have measured fuel consumption for automobiles in America has been in miles per gallon (mpg). Since many countries are use the metric system, there has been a shift away from using mpg. Now this sounds like a great move, since the metric system is far superior to its imperial counterpart, but instead of simply converting miles to kilometers and gallons to liters, giving us kilometers per liter (km/l), we are now stuck with liters per hundred kilometers (l/100 km). It may seem like an insignificant difference, but there is a movement aimed at extinguishing mpg from the face of the Earth and replacing it with l/100 km. So if there’s people out there making websites and handing out pamphlets, there must be an obvious advantage to using the l/100 km system, right?

Proponents of the l/100 km system, or 100kers, try to confuse you by asking questions like, “Which saves more gasoline, going from 10 to 20 mpg, or going from 33 to 50 mpg?” Then they tell you that the answer is that the first option saves five times as much gas as the second. Upon hearing the correct answer, you are then shocked and upset, confused by why a 10 mpg change is much greater than a 17 mpg change. Instead of questioning why math is so dumb, let’s answer a better question: what is a consumption per unit system actually measuring?

Let’s face it, most people don’t know their mpg, let alone their km/l or l/100 km. When you ask someone what kind of mileage their car gets, the answer is something like, “I put $40 in there every two weeks,” or, “I can go three weeks before I have to fill up.” These answers are worse than useless, as we are not told the value of any variables in the equation.

Before we continue, let’s get a handle on what we’re measuring by calculating the mpg for an average car at the pump. Imagine that, after starting with a full tank of gas, you drove your Chevrolet Cavalier 300 miles, then decided it was time for a refill. After topping up, the display shows 10 gallons pumped. To find out how many mpg your car gets, you simply divide miles driven by gallons pumped (300m/10g) which gives us 30 mpg. What this number means is that for every gallon of gas you pump into your car you can drive 30 miles. Confused? No.

Similar to the previous example, let’s pretend that you drove your Cavalier 450 kilometers and then pumped 30 liters of gas to fill it up. Now to get your km/l you preform the same calculation as you would to get mpg, except you are dividing kilometers driven by liters pumped, which results in 15 km/l. However, if you’re a 100ker, you will divide liters pumped by kilometers driven, then multiply the answer by 100, resulting in 6.67 l/100 km. The meaning of this number is less obvious to the average driver, unless you are only driving in 100 kilometer increments.

So since we now have a grasp on how to calculate each of these measurements of mileage, let’s see if they are really that different. mpg measures miles driven per gallons used. km/l measures kilometers driven per liters used. l/100 km measures liters used per 100 kilometers driven. The third option is slightly different than first two because it is actually just the reciprocal of the second option multiplied by 100. The reason they use 100 kilometers is that dividing liters used by kilometers driven gives you a very small number between 0 and 1, as all modern consumer vehicles drive more than one kilometer for every liter of fuel they use. So if the third option is just the second one flipped upside-down, why all the debate? Let’s do some graphing. For the sake of comparison we are going to leave out mpg and use only kilometers and liters.

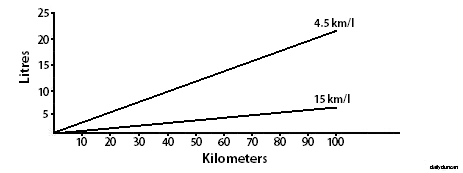

The graph above shows the mileage, or, more accurately, the kilometage of two vehicles. All vehicles plotted on this graph will show a straight line, unless they have inconsistent fuel consumption, which they don’t. The first line shows a vehicle which gets 4.5 km/l, likely a sport utility vehicle or large truck, while the second line represents a small sedan, showing an impressive 15 km/l. We can see that after driving 100 kilometers, the first vehicle consumes around 22.2 liters of fuel, while the second consumed only 6.67.

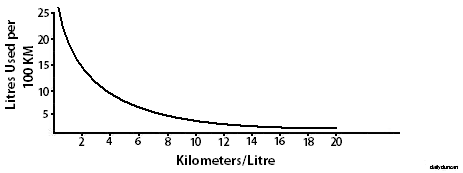

The confusion begins when 100kers compare the two lines on the graph and wonder why the difference in (km/l) is not the same as the difference in liters used. Basically, the amount of fuel used should not vary as you move along the graph. What they want is a graph which compares km/l to liters used, but you can’t make that graph because there’s no way to know how many liters you are using unless you define how many kilometers you are driving. So we will plug in 100 km and graph how many liters are used every 100 kilometers as the km/l changes.

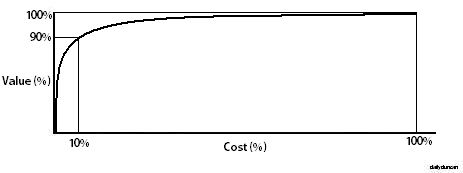

Now we have a nice graph which we can use to see how many liters we are saving as we adjust the km/l, just what the 100kers want. But why should everyone in the world use a system that is more difficult to calculate and less obvious in terms of daily use? At its core, the issue is that these people think fuel economy should always be used to determine how much fuel you can save when driving a set distance. What if you wanted to know how many kilometers you could drive with a set amount of fuel, or how many liters you will burn when driving any distance other than 100 kilometers? Apparently these questions aren’t worth asking.

The l/100 km method is also inconsistent with our fuel consumption language, since as fuel economy increases, l/100 km decreases. A vehicle that gets 2 l/100 km is twice as fuel efficient as one which gets 4 l/100 km. In addition, as fuel economy improves in the future, the number may drop below 1, which means that we could see hybrid sedans advertised with a fuel consumption of 0.33 l/100 km. Eventually we will switch to l/1000 km, all because of those selfish short-sighted 100kers.

So if you think that every motorist should do more calculations and use an ambiguous fuel consumption system which approaches zero as fuel economy increases, just so those who analyze fuel economy don’t have to do extra math, then go on, go the wrong way. We never wanted you with us anyway.