“If you would have seen what I’ve seen, then you’d understand.”

His gaze leaves the room as memory engulfs him. Hell is not a fantasy, but history. Visions of severed limbs and hollow faces wash over his fragile heart like lifeless bodies breaking against distant shores.

Our memories are as much a part of us as our DNA. Both define who we are, and just as we cannot edit our genetic code, we cannot rewrite our history. It’s impossible to escape that which we have endured, and so we shoulder burdens of fear, anger and remorse. We like to imagine that we choose who we are, what we think and how we feel, but the reality is that we are blessed, scarred creatures, refined and haunted by our past.

We dare not speak of war to the veteran or of love to the widow. We dare not grumble about bright lights to the blind or stagnant wages to the unemployed. We would never fret over a pimple in the presence of those who are disfigured, and we would not make light of a disability in the presence of someone who suffers its reality every day.

Those who have experienced intense, life-changing events or conditions often develop an increased sensitivity to such things, and when we’re in the presence of someone who has been through a traumatic experience, we also become sensitive to that experience.

This is why ads that depict starving, suffering children have little effect on healthy, first-world citizens. We certainly don’t doubt that those children are suffering or that they need help, but they are outside of our proximity. While televisions may transmit images and sounds effectively, they do not transmit experience, and they do not put us in the presence of those suffering children.

The problem is not that we have been desensitized to these things, since that would imply that we were once sensitive to them. Neither is the problem that we are insensitive, for we can certainly feel compassion, empathy and other emotions. The truth is that we aren’t sensitive to these issues because we have never been sensitized to them. Without living in poverty or experiencing starvation, we can’t help but underreact. We all know and agree that poverty and starvation are bad, but we know it in a theoretical, moral sense; we don’t know how it feels to be poor and starving.

The simple fact that something is true usually isn’t enough to invoke a reaction. This is why advertizers use music, drama, sex, controversy and comedy to provoke us. They’re trying to make us understand, make us imagine enjoying the ice-cool soda on a hot day or driving the elegant, powerful sports car down winding rural roads.

The impotence of mere truth is also why we find it much easier to hurt people we can’t see or don’t know. We’re much more likely to berate others on the Internet, steal from a faceless corporation, get angry at other drivers or even crush the dreams of unknown opponents in a competition. It’s not that we believe that these actions are any less wrong in such situations, but we don’t have to look someone we know in the eye when we commit them.

Although we might believe that an action is wrong, the severity and impact of that belief changes depending on our company. We never swear in front of our grandmother, we don’t say retard near those with mental disabilities and we wouldn’t complain about our big feet to someone with no legs. Our sensitivities are constantly fluctuating as we engage with different people. This basically means that each of us suffers from a form of dissociative identity disorder, since we are constantly changing from one person into another.

Some would argue that the problem is the increased sensitivity of those affected by traumatic experiences. They might say that it’s unfair and unreasonable to expect others to be sensitive when they only became sensitive through personal experience. This is a sensible conclusion, but it ignores a simple, yet important question: which level of sensitivity is correct?

Consider the story of a man who tragically lost his home and family in a fire. To him, having smoke detectors, a fire extinguisher and an emergency escape plan now seems extremely important. After dealing with his loss, he chooses to begin a crusade to educate others on fire safety. Because of his experience, the man’s concern is heavily weighted toward this issue. This doesn’t mean that his warnings are invalid or exaggerated, only that his ability to perceive the truth of the danger of fire was revealed by his proximity to such events. He is now subject to increased sensitivity and awareness of the issue. He no longer finds certain jokes or comments funny and reacts to imagery of fire and smoke differently than another person might. He is now subject to what are called trauma triggers – experiences that trigger a response from someone who has been traumatized.

Critics of this man’s position might point out his lack of concern for healthy living or earthquake safety. After all, while it’s true that fire safety is important, there are a multitude of threats endangering our families. These people would argue that the man’s perception has been tainted and that he now possesses an intense bias toward fire safety. In this civilized, scientific era, empirical knowledge is supreme, and those who allow bias, emotion and experience to influence their decisions are considered foolish, since we can easily show the inconsistencies in their positions.

Others would maintain that the man’s crusade for fire safety, though extreme, is an important contribution. They would agree that his reaction is emotional and possibly unreasonable, but they would never discourage or criticize him for focusing on only one issue. This is probably the most acceptable and popular position, but it ignores the profound possibility that this man’s vision is not distorted by his experience, but clarified. What if the man’s crusade to promote fire safety is merely a reasonable reaction from someone surrounded by people who don’t understand what he now sees so clearly? It may be that he is still blind to other dangers, but this only means that we are even more blind.

So what is the proper reaction from unsensitized folk, given what we’ve learned? Here are some options:

- Ignore the issue and continue adapting to the sensitivities of others without feeling them ourselves.

- Force ourselves into acts of charity regardless of our sensitivity to the issue.

- Immerse ourselves in suffering to gain sensitivity.

The first solution is obviously wrong because it’s boring and has the word ignore in it. Aside from that, it evades the question of whether or not suffering enlightens or misguides us.

The second option is a good choice if you’re interested in resuming your normal life while appeasing any sense of guilt or obligation to others. It’s true that acts of love done without love still make a difference, but they ignore the systemic problem of a lack of concern for others, which will eventually lead to increased suffering.

The final choice seems frightening and overwhelming, but we may be able to sensitize ourselves without bringing suffering on ourselves. As we mentioned earlier, simply being near someone is enough to temporarily grant us sensitivity, so perhaps we can permanently sensitize ourselves by allowing them to share their lives with us. This is possible because there are more ways to experience something than personally living through it.

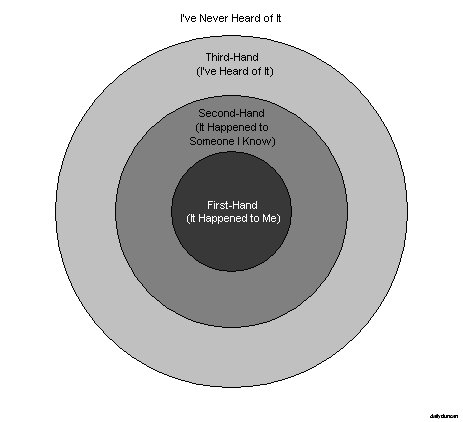

The image above shows that there are actually four levels of experience. Those in the first, outer-most level have absolutely no experience with the subject. They’re usually fearful, curious and skeptical of the new experience, since they haven’t even heard of it before.

The second level is the one that most of us would would identify with, and it’s one of the two we’ve been discussing. All of us have heard of cancer, poverty, AIDS and political persecution, but we’ve never experienced these things, and we aren’t close with anyone who has. We may have casual acquaintances or distant relatives who have lived through these experiences, but we don’t know them well enough to understand their situations.

Let’s skip ahead to the fourth and inner-most level, which is another one we’ve been talking about. Those in this level have personally experienced suffering and exhibit the increased sensitivity we’ve already discussed.

The third level of experience is the path to sensitivity we’re looking for. People with second-hand experience have shared a close relationship with someone in the first level. An example might be a person whose immediate family member suffered a serious illness. Some might argue that the line between first and second hand experience is blurry, and that’s precisely the point. By sharing in the suffering of others, we can permanently adopt their experience and sensitivity. We have done more than witness the suffering of another, we have endured it with them.

Now let’s return to the question of whether suffering enlightens or misguides us. First, by asking such a question, we’re making an assumption that there is a default perception. But just as there is no correct price of fuel, there is no correct way to perceive the world. Again, some would say that the correct understanding is one of unbiased empiricism, but a purely empirical worldview would remove love, honesty, morality and human value from the equation. Without these things, we cannot discern whether or not suffering is bad or human extinction is good. On top of that, empirical knowledge is merely something that some of us prefer, so someone who promotes empirical knowledge is actually revealing their biased toward empiricism.

To say that there is no correct way to perceive the world seems a bit extreme, but we’re not talking about moral relativism, religious pluralism or the rejection of scientific theory. We’re not here to debate the existence of reality; we’re talking about the lens of experience through which we view the world. To put it scientifically, we’re talking about the combination of chemicals and electrical impulses in the brain that make up our attitude, outlook, emotions, values and overall state of mind.

In contrast to the more extreme examples of suffering we’ve used, here are some minor influences that are constantly altering our perception:

- Confusion

- Pain or discomfort

- Lack of sleep

- Hunger or thirst

- Drugs and alcohol

- Caffeine

- Exercise

- Sexual arousal

- Joy

- Anger

- Boredom

- Solitude

- Social awkwardness

- Confidence

- Uncertainty

- Greed

- Guilt

- Obligation

- Competition

- Inspiration

As we can see, our outlook on life is changing every moment. Even drinking a glass of water or taking a few seconds to look out the window can make us feel better, and a simple compliment from a stranger can change what we think of ourselves. Likewise, staying up too late or encountering an irritating person can put us off, and receiving a bill in the mail can change our attitude toward finances.

A person may try to argue that our perception is correct when we are free from all of these influences, but not only is it extremely unlikely that we would be able to attain such a state, a position of perfect balance would also be the result of external influences. Even the air we breath makes us who we are, for variations in the oxygen content of our environment affects our physiology. Perhaps oxygen is actually a hallucinogen that causes us to imagine that our existence is meaningful. Whatever the case, our perception is obviously unstable.

In addition to the our normal fluctuation, intense experiences induce brief states of extreme emotion. Having valuable property stolen can affect us for life, but it also affects us in a more powerful, temporary way when it initially occurs. Learning that we have lost important, irreplaceable items will cause us to realize the insignificance of our other problems. But then learning that a family member has been diagnosed with a life-threatening disease makes us immediately forget our stolen property.

So not only is our perception vulnerable to minor temporary changes and powerful permanent changes, it’s also subject to even more powerful temporary changes brought on by the same experiences that affect us for life. And in these moments of extreme emotion, are really experiencing clarity? And if we are, how can we say that this is the correct perception, since it’s impossible to maintain such a view? Well, if there’s no correct way to perceive the world, and if our perception is constantly and sometimes drastically changing, it would seem impossible to determine whether traumatic experiences enlighten or misguide us. But just because we can’t be the best, it doesn’t mean we can’t be better. Perhaps instead of attempting to identify a perfect state of understanding, we should merely be seeking to learn what we can from those who suffer.

Since determining a complete and sound moral code is beyond the scope of our discussion, we can temporarily suspend philosophical inquiry and appeal to the general understanding that whatever results in the greatest good for the most people is right and that we should treat others the way we want to be treated. Now if no lens of perception is correct, then perhaps we should view the world in whatever manner results in the greatest good and increases our ability to treat other the way we would want to be treated. In other words, our perception should prioritize the greater good and cause us to feel empathy for others.

So how do we do this? A good strategy would be to look at the world through the eyes of as many people as possible. By sharing in their suffering through second-hand experience, we can align our priorities with theirs and become genuinely sensitive to their situation. In doing so, we generate empathy, which causes us to treat them, and others in similar situations, with the same sensitivity that we now share. And in addition to all this, we should never forget to be sensitive to the unsensitized, for they are merely seeds that have not yet sprouted.

Stop changing who you are based on who’s around you, and stop trying to do what’s right when you don’t care. Get sensitized.