In corporate boardrooms aloft city streets, evil executives scheme and plot. Their aim, of course, is to convince the consumer to choose their product over that of their competitor. This is no easy task, however, since today’s consumer pays little attention to most advertisements. Every company proclaims that their product is the fastest, cheapest, safest or most efficient of its kind, but today’s intelligent, educated consumer sees right through these straight-forward tactics. Simply stating that your product is superior doesn’t quite cut it anymore.

This is why companies have begun to explore alternative methods for attracting potential buyers. One such tactic is offering a membership that allows customers to accumulate points that may then be redeemed for various goods and services. The concept of a rewards program for members is indeed a brilliant one, as it offers an incentive for customer loyalty as well as a database of clients ready to be harassed by phone calls during their dinner. Apart from the minor inconvenience of call center drones and requests for membership at the till, this system has one massive problem: inconsistent point value.

Every program has a different value for its points and dispenses them at a different rate. Some companies offer one point per dollar spent, some offer 1,000 times that amount. Most customer memberships offer some kind of bonus for signing up because they know that customers do not want to waste their time filling out tedious forms. At every turn, employees politely offer you admission to their rewards program, touting the wonders that lie within. Rejecting their offer without a sound explanation is dangerous, as these point peddlers are often quite adamant that you understand what a generous gift they are bestowing on you. What they often fail to advertise is the rate of accumulation and practical value of the points. Without these two key pieces of information, how can one determine whether or not it’s actually beneficial to apply for membership? The bonus for admission could be 10 points or 10,000,000 points; it makes no difference unless they clearly define the point value in practical way.

Another disappointing feature of customer memberships is the point redemption system, which is usually complex and indirect, like riding the bus. The selection is often lackluster, offering customers a choice between a package of used napkins or 25% off pork snout with a purchase of 5 or more. Some systems are better than others, so let’s look at a few successful variations of the point-rewarding program.

One avenue to a viable point-reward system is assigning the points an actual dollar value. Some stores do this by offering store currency, usually printed on paper, to customers after their purchase. The value of this currency is often minimal, but at least the redemption is direct and consistent. Unfortunately, the production of this currency can be more costly than the currency’s value, which results in higher operating costs and, ironically, higher prices. This store currency functions in a similar way to a coupon, though it is more effective because it does not require the customer to purchase certain items at a certain time, and it can be accumulated.

Coupons have often been considered a legitimate tactic for those with a tight budget, but this is only because these people do not consider the cost of cutting coupons. Coupons cost time. Shopping around for the lowest price and clipping coupons may appear to save money, but only if the time spent has no value. Time does have value, and a the value of a person’s time is defined by their job. If their position pays $20 per hour, then they must be saving at least $20 for every hour of bartering and coupon hunting, otherwise they would be better off working.

Another option is the air miles program which many companies now use to attract and reward customers. This is an ingenious idea, because it compensates faithful customers with a vacation that will result in additional spending. Unfortunately, somewhere along the line the value of air miles was corrupted. One air mile does not always translate into an actual physical mile of travel aboard an airplane. Air miles may now be redeemed for gift certificates, car and hotel rentals or even a car wash. Since the value is now arbitrary, your precious collection of air miles could take a nose dive at any moment.

A few companies have taken customer membership in another direction. Instead of offering free memberships and rewarding customers for their purchases, the membership has an annual fee and it merely grants the member access to the store. By comparison, this membership may seem inferior, but it is extremely effective. By charging potential customers a fee simply to enter the building, the member gratefully accepts the “reward” of shopping at their store. Through preying upon the human affection for exclusivity, the company is able to squeeze a few bucks out of its customers in exchange for allowing them to buy its products. What a deal.

Still another way of using points is by offering them in exchange for money. Some online stores require their customers to purchase points or tokens in order to buy their products. This method is commonly used to disguise the actual cost of products and remove the negative feeling of spending money, for it is much easier to part with points than dollars.

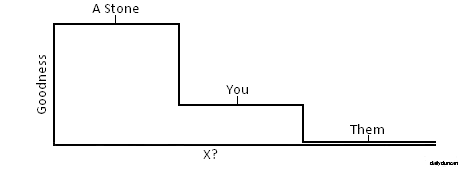

Regardless of what method is used to dispense the points, they should come in one of two forms. Point value should either be based on actual currency value or it should be reduced. In this instance we are talking about mathematical definition of reducing. The points should be reduced to the lowest common denominator, which is the lowest number of points that can be earned or spent. If a membership program rewards members with 1,000 points for a minor purchase and the cheapest redeemable item is 50,000 points, then they should reduce the point value by a multiple of 1,000. If a company is going to reward members with points or air miles, it should do so in a manner that does not attempt to exaggerate or distort the value.

This principle should be applied to all areas. A great example would be sports, since many of them suffer from convoluted scoring systems. Tennis, for example, awards 15 points for each point scored. In basketball and American football, teams may score multiple points at once, but the minimum number of points a team can score is 1, making them good examples of a reduced point system. In professional boxing, the fight is judged round-by-round, with the round winner receiving 10 points unless an infraction occurred. By always awarding the winner the same amount of points, the system is functionally reversed from that of traditional judging. Instead of rewarding an athlete with points for a maneuver, the opponent is punished with fewer points. In addition, the round loser is rarely awarded less than 9 points, and its extremely unlikely to see less than 8.

Whether it’s rewards programs or sports, even school grades or fuel consumption, it’s important to establish a system that does not unnecessarily complicate. Part of the purpose of mathematics is to simplify the functions of the universe so that we may understand them, but by using needlessly complex systems, we are creating inefficiency and inconsistency and becoming enemies of progress.

Next time someone asks you to subscribe to a membership program, ask them the value of their points.