What makes us who we are?

This question seems intriguing, but it’s actually far too vague to have any real meaning. This is also the case when people ask, “what is the meaning of life?” They think they’re being insightful, but without specifying what they’re trying to discover, the answer is made indiscernible, and the question becomes useless. To illustrate this problem, try to determine the meaning of the subject in any of the following questions:

- What is the meaning of broccoli?

- What is the meaning of basketball?

- What is the meaning of five dollars?

- What is the meaning of a question that asks about the meaning of life?

As we can see, asking such poorly-phrased questions leaves far too much room for interpretation. It’s likely that they meant to ask something like, “for what reason was life created?” or “what is the purpose of human existence?” Now let’s return to our original inquiry, improving its structure in order to allow for a meaningful answer.

What properties possessed by an individual human distinguishes them from other humans?

Even this more pointed question still retains many different avenues of response. After all, a fingerprint is unique and distinguishes each human from all others. But the question seems philosophical in nature, so it probably doesn’t aim to address the mere physical. Its phrasing also suggests that there’s more than one correct answer, though we’re probably just looking for the most interesting and insightful one. Let’s try again.

What feature of a person contains the most crucial and meaningful components that make them a unique individual?

Now we’re onto something. We all know that everyone is unique, and we can easily distinguish one person from others, so let’s start our question for a solution by examining the ways that we tell each other apart and see if one of them satisfies our inquiry.

The first and most obvious way that we recognize each other is by our appearance. It’s true that we’re covered by clothing and makeup much of the time, and it’s also true that each of us has our own fashion sense that we pretend is unique, and yet we’re still able to recognize each other in a swimsuit or bizarre costume. This is because there’s a special part of the brain responsible for facial recognition, and it helps us tell others apart. However, few would agree that our bodies or our faces make us who we are. In the 1997 action movie Face/Off, FBI agent Sean Archer and criminal mastermind Caster Troy (played by John Travolta and Nicholas Cage irrespectively) have their faces switched. While the premise and execution of this film is obviously bad, it teaches us that we aren’t defined by our appearance. There are also those who tragically suffer amputations or facial deformation, and while they may ask serious questions about their own identity and purpose, others certainly identify them as the same person.

Those who subscribe to a materialistic view would likely argue that it’s our genetics that make us who we are. According to them, since everything can be explained by natural processes, then everything about us is derived from our genes: our appearance, ideas and abilities. On top of that, each of us has our own unique genetic code, or do we? Identical twins actually share the same DNA and, while irritatingly similar, they aren’t the same person. If two people with identical genetics can be distinct, then this can’t be what defines us.

The world is full of those whose quest in life is fame and wealth. In many ways their identity is tied to their notoriety and possessions, but even pop culture recognizes that money doesn’t define who we are. In her autobiographical 2001 hit single Jenny From The Block, Jennifer Lopez pleads with audiences, “don’t be fooled by the rocks that I got,” and goes onto claim that despite her wealth and status, “[she’s] still Jenny from the block.” This implies that her identity remains static despite the fact that she, “used to have a little, now [she] has a lot.”

If it isn’t her wealth and fame, maybe Ms. Lopez’ talents and accomplishments as a dancer, singer, songwriter, author, actress, fashion designer and producer that define her. After all, each of us possess unique skills and abilities that make us special (at least that’s what our mothers told us). It’s true that our skills, abilities, achievements, vocations and interests define us to a degree. An example of the value we place on our job is the fact that the first question we ask a new acquaintance is often what do you do? Many of us derive our identity primarily from our profession. However, when we encounter failure, disability or retirement, we’re still us.

So clothes don’t make the man and neither does the body. Our genes don’t make us unique individuals. On top of that, wealth and fame don’t define us and neither do our abilities or achievements. So what could it be? Perhaps we can find the solution by examining cases of people who are no longer identified as the person they once were. Unfortunately there are millions of examples of such cases.

Dementia comes in many forms, the most common being Alzheimer’s disease. Those suffering from dementia experience a number of symptoms including memory loss, memory distortion, speech and language problems, agitation, loss of balance and fine motor skills, delusions, depression and anxiety. These symptoms are caused by changes in the brain brought on by nerve cell damage, protein deposits and other complications. In advanced cases, the person may become unrecognizable to loved ones. Visiting family members may be shocked to find their relative or friend using abusive language, exhibiting violent aggression or making inappropriate sexual comments.

Brain damage can also produce equally drastic changes in people. In her article After Brain Injury: Learning to Love a Stranger, Janet Cromer details the story of her husband, who suffered anoxic brain injury. She discusses the impact of brain injury on her husband’s memory, communication, behavior and personality. She notes that the experience is like getting to know him all over again, summarizing it this way: “Imagine feeling like you’re on a first date even though you’ve been married to this person for… 30 years?”

It’s clear that our identities are largely defined by our personalities. The things we love and hate, the ways we think and act, even our way of standing perfectly still – they all define who we are. When these things change, we change. But there’s more to us than simply what we think, do and say.

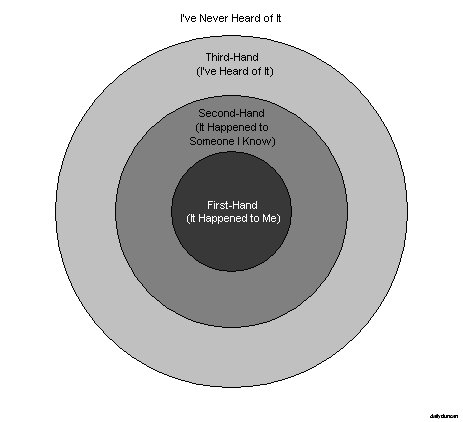

The other way that we can observe changes in identity is though memory loss. In addition to the aforementioned cases of dementia, retrograde amnesia can also impair or rewrite personal identity. While most of us have no experience with amnesia, it’s obvious that a loss of knowledge of identity is a loss of identity. After all, how can you be someone you’ve never heard of? But memories don’t just allow us to recognize our own identity, they also define us, for we are obviously and seriously affected by our experiences. Brain scans reveal that those who have been traumatized, especially at a young age, actually show clear physical changed in the brain.

Though it’s pure fiction, there are cases in which we accept that a person’s identity has changed. Hollywood provides us with many examples of instantaneous change of identity due to mind transfer. In the 1976 film Freaky Friday, a mother and daughter miraculously have their memories switched (as well as their personalities). While the story may not be the most plausible, we clearly understand that the two characters are no longer themselves. 2001’s K-PAX tells the story of an alien being called Prot who inhabits the body of a human named Robert Porter. At the end of the film, the alien abandons its human form, leaving behind a catatonic Porter. Upon his departure, Prot’s former body is no longer recognizable by his friends, one of whom remarks, “That’s not Prot.”

These examples also illustrate how important memory is to our identity. Without the transference of memory, the characters would retain the knowledge of their past, including their own identity. And this is precisely why the existence of reincarnation is largely inconsequential. If we possess only the memories of ourselves, then it doesn’t matter if our life is the continuation of another. If a person experienced reincarnation or a mind transfer, but did not retain any memory, then they would be unable to identify as anyone but their current self and would therefore possess a unique identity. So don’t do good for the sake of your reincarnated self, for the being you will be will not be you.

And so we have our answer: it is our personality and memory that make us who we are. And although there is great uncertainty about how it actually works, these features are produced and stored in the brain, which somehow projects consciousness (also known as the mind). Our minds allow us to perceive, think and imagine, and while its existence is arguable metaphysical, the mind gives rise to identity. So identity is actually stored in and generated by the brain.

Now we can rest in the knowledge that our identity is safely locked inside a squishy mass hidden behind a quarter inch of bone. Unfortunately the brain remains a very mysterious and peculiar thing. In part II we will explore some of the curiosities and limits of this mighty organ that defines us.