When the last whale washes up on shore,

When the last elephant is poached for its tusks,

When the last eagle flies over the last crumbling mountain,

We will mourn.

But who will mourn the snail, the spider, the mouse?

The mole, the gnat, the tick, the grouse?

The fly on our windshield, the ant beneath our feet?

Or the swarms of rodents infesting our streets?

People hold many different views on the role and value of animals in our society, but one thing that they all agree on, whether they would admit it or not, is that some animals are more valuable than others.

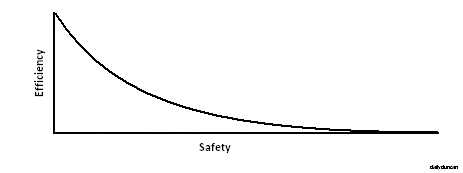

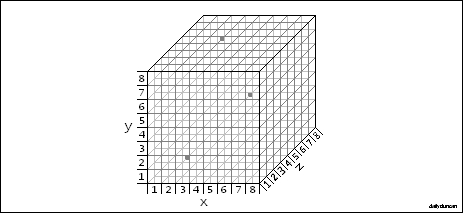

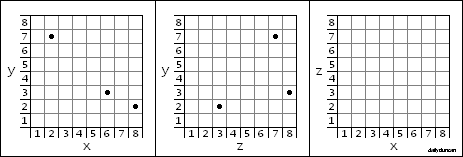

Every species has a value, and that value is based its intelligence, size and majesty. We will now look at each of these features in order to better understand how to rank an animal’s value. Let’s start with the least important feature, intelligence.

When animals show intelligence, we see something of ourselves in them, and a kinship is created. When we watch a raven solve a puzzle, a dolphin swim along side a vessel or a dog wag its tail with glee, we can’t help but project our emotions onto those creatures and treat them as a fellow member of the elite league of intelligent creatures. Conversely, when we watch an animal do something stupid, like when a bird flies in front of a car, a fish jumps out of its aquarium or an insect flies into our mouth, we can’t help but feel estranged from such creatures. We just can’t imagine what, if anything, they were thinking, and so we treat them with disdain.

Because humans are both the most important and the most intelligent animal, we might think that intelligence is the most important feature, but there are many animals that show high intelligence that are not valued very highly, most notably pigeons and rats.

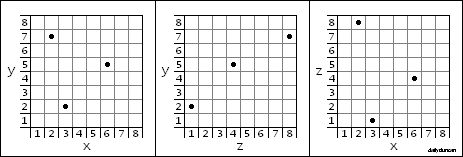

The second most important feature is size. When an animal is small, we tend not to care about it. When was the last time we shed a tear for a bee or a louse? It can’t be a coincidence that all of the creatures adored by animal activists are relatively large. As an example, if we were to rank the importance of a rabbit, a snail, a cow, a whale and a salamander, the result would be as follows:

- Whale

- Cow

- Rabbit

- Salamanter

- Snail

The reason why size is important is not exactly clear. Part of the reason could be that we cannot relate to tiny creatures because we cannot easily see them, which makes it difficult to understand them and observe their complexities. Another reason could be that smaller animals tend to exist in large numbers, which makes them seem expendable. It could also be that small creatures do not have much, if any, blood, so their deaths are not gruesome and traumatic. Size matters, but sometimes small animals can have big value, as is the case with seahorses, hummingbirds and most infant animals.

The final and most important feature in animal value is majesty. Majesty is why we prefer parrots over possums and bears over barracuda. The majesty of an animal has many facets, including age, adorability, ferocity, beauty, rarity, strength, fragility and peculiarity, but it is hard to define concretely. There are, however, some general guidelines that majestic animals tend to follow. Here are a few of them:

- Don’t carry diseases.

- Don’t sting or bite humans.

- Don’t have small, soulless eyes.

- Don’t be belligerent and numerous.

- Don’t eat human food.

- Don’t suck blood.

- Don’t screech or buzz.

- Don’t have more than four legs.

- Don’t crawl or slither.

- Don’t secrete anything.

Majestic animals don’t do these things; they soar, roar, gallop, glide, splash and sing. Animals that don’t follow these guidelines are subject to hatred and revulsion. One creature that is currently experiencing the negative effects of having a low animal value is the mosquito.

Bill Gates, a well-known wealthy person, has declared war on the mosquito because it spreads malaria, a disease that is responsible for hundreds of thousands of human deaths every year. Gates is bent on the eradication of these helpless insects, which are not defended by animal rights groups simply because they have little value.

So be careful, little creatures, what you do.