Despite how insightful the idea may seem, the opposite of love is not indifference. The opposite of something isn’t nothing, it’s something that is opposed or contrary to it. If the opposite of love is indifference, then the opposite of every emotion must also be indifference. Though cold is technically the absence of heat, the opposite of a high temperature is a low temperature, not a mild temperature. So what are opposites, exactly, and how do we determine their identity?

Although we all understand what an opposite is, defining it is a little tricky. For example, everyone knows that the opposite of evil is good and that good triumphs over evil, but how do we define good in relation to evil? Good is not merely the absence of evil, neither is it something totally dissimilar; it is the inverse, the nemesis or, expressed mathematically, evil*-1.

There are actually two distinct variations of opposites: polar opposites and binary opposites. Examples of polar opposition would include an inch and a mile or constipation and diarrhea, because they reside at different ends of a spectrum. Polar opposites are simply the inverse of each other and usually aren’t very difficult to discern.

Binary opposites, however, are not commonly identified as part of a spectrum, but are defined in relation to a counterpart. Men and women, for example, are opposites not because they are contrary or inverted, though in some ways they are, but because they make up the gender binary. Using this interpretation, the opposite of night would be day and the opposite of a hand would be a foot.

Sometimes a subject may have more than one binary opposite. Although this seems nonsensical, we must remember that most things can be categorized in different ways. For example, a man is not merely defined as one of two sexes, but as a human, an intelligent being, a creature, a collection of organic matter, an imperfect being, a creator, a destroyer and an explorer. So depending on the context, the opposite of a man could be an animal, an inanimate object, an angel, demon, god or ghost, a force of good or a force of evil. Likewise, the opposite of a chicken could be an egg, but the opposite of a chicken stir fry would probably be a beef stir fry.

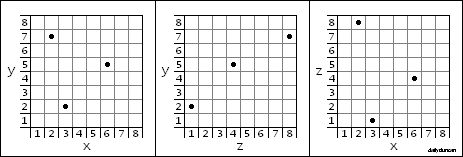

Now what happens when we add attributes to the subject? A tall man is an example of something that has both a polar and binary opposite.

| Tall |

Man |

| Tall |

Woman |

| Short |

Man |

| Short |

Woman |

Here we see the different potential opposites of a tall man. The opposite of the subject, man, is woman, and the opposite of the attribute, tall, is short. So how do we determine the opposite of a tall man, since it’s comprised of two components?

There are three dominant theories which dictate how we derive the opposite in a case such as this. The first is opposite subject theory, which states that we should find the inverse of the subject, resulting in tall woman. The second is known as opposite attribute theory, and it requires us to invert only the attributes, which produces short man. The third theory is called complete opposite theory, and it states that we must find the opposite of both the subject and the attribute(s), giving us short woman.

One idea that has fallen out of favor in recent years is opposite attraction theory, which uses the laws of attraction to deduce opposites. This theory is very fun and works great in the realms of romance, positive thinking and electromagnetism, but it doesn’t help much in our case. Each of our three dominant theories has its own strengths and non-strengths, which we will be revealed through examination our next example: a baby boy playing. Let’s see how each of our theories decodes the opposite in this scenario.

| Baby |

Boy |

Playing |

| Baby |

Boy |

Working |

| Baby |

Girl |

Playing |

| Baby |

Girl |

Working |

| Adult |

Boy |

Playing |

| Adult |

Boy |

Working |

| Adult |

Girl |

Playing |

| Adult |

Girl |

Working |

Opposite subject theory would have us invert the subject, boy, resulting in baby girl playing. This theory works very well when dealing with subjects with obvious polar or binary opposites, but what about something that doesn’t have a clear opposite, like a paperclip, cloud or dishwasher?

The second option simply asks us to invert all of the described attributes, leaving only the subject unchanged, which gives us adult boy working. For a long time this theory worked fine and the land was green and good, until the crystal cracked.

A fringe theory broke off from opposite attribute theory, and it asked us to find the primary attribute of the subject and invert only that attribute. In this case, the primary attribute would be baby, since it most intrinsically and decisively defines the subject, boy, so we would get adult boy playing.

The difficulty with primary attribute theory is discerning which attribute is primary and whether or not it’s actually part of the subject. Some might argue that the primary attribute in this case is boy and that the subject is actually baby, but the term baby is more commonly used as an adjective to describe things like baby food, baby clothes, baby steps and baby baboons.

However, a big blue fish has two seemingly equal defining attributes. This means that there is either no correct opposite or a number of equally correct opposites, which may cause one to question the existence of moral absolutes.

The third option, complete opposite theory, would have us invert both the attributes, baby and playing, as well as the subject, boy, which produces adult girl working. Although this answer is very convincing, it gives us a result that is totally dissimilar to the original. This method is surely logical, but it breaks down when we apply it to certain well-known opposites.

We all know the opposite of walking forward is walking backward, not running or crawling backward. We also know that the opposite of a human getting older is a human getting younger, not a non-human getting younger. This is because opposites must share a point of reference, which is usually the subject. If they don’t, then we end up with two things that are totally different, which is not what opposites are about. This method also suffers from the same problem as opposite subject theory, since both require the subject to be inverted.

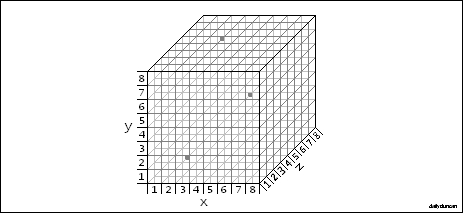

Now let’s take a look at both of the types of opposites as well as each of the theories we explored. In order to help us understand opposites more clearly, let’s use mathematic expressions for both polar and binary opposites with each of the theories applied.

| Expression |

Polar Opposite |

| Subject |

Attribute(s) |

Primary Attribute |

Complete |

| x |

-x |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

-x |

| x+1 |

-x+1 |

x-1 |

x-1 |

-x-1 |

| 5x-5 |

5(-x)-5 |

-5x+5 |

-5x-5 |

-5(-x)+5 |

| 1(-x+1)^-1 |

1(x+1)^-1 |

-1(-x-1)^1 |

1(-x+1)^1 |

-1(x-1)^1 |

| Expression |

Binary Opposite |

| Subject |

Attribute(s) |

Primary Attribute |

Complete |

| x |

y |

Not Applicable |

Not Applicable |

y |

| x+1 |

y+1 |

x+0 |

x+0 |

y+0 |

| 5x-5 |

5y-5 |

5x-5 |

5x-5 |

5y-5 |

| 1(-x+1)^-1 |

1(-y+1)^-1 |

0(-x+0)^0 |

1(-x+1)^0 |

0(-y+0)^0 |

As we can see, we get very different answers depending on how we go about getting our opposites. And even when we use numbers, opposites are not easily determined. Although in these examples we can simply use the order of operations to determine the primary attribute, we still run into difficulty with multiple operations of the same order.

It’s easy to see that the polar opposite of x is -x, and the binary opposite is y. Likewise, the polar opposite of 1 is obviously -1, and the binary opposite is even more obviously 0. However, while the polar opposite of 5 is clearly -5, there is no binary opposite to such a number. Just like dishwashers and many other real-world examples, most numbers don’t have binary opposites, which means we must use the polar opposite, since the alternative could mean inverting nothing at all. Now we see that no opposite type or theory is fully adequate, since they all have exceptions.

So how do we know when to use polar opposites and when to use binary opposites? Determining the opposite of an attribute is relatively simple, since adjectives usually fall on a spectrum. For subjects, however, one tactic we can use is to test for an obvious binary opposite before exploring polar opposites. Since not all subjects have a binary opposite, it would make sense to first test to see if it has a well-known counterpart.

Now which theory is most versatile and consistently produces meaningful opposites? Opposite subject theory can force us to conjure up ridiculous nonexistent beings or mechanisms to find an opposite, and opposite attribute theory can produce results that are too dissimilar to be recognized as an opposite. Complete opposite theory, while perhaps the most logical, suffers from both of these complications. Opposite primary attribute theory, on the other hand, allows us to avoid silly subject opposites and also yields recognizable and meaningful opposites.

So how do we resolve subjects that have multiple attributes but no primary attribute? In other words, what if our adjectives aren’t cumulative? Well, just as a subject may have more than one opposite, there can also be more than one opposite when there is no primary attribute. If both attributes are equally describe the subject, a wise strategy would be to choose the one that is most easily inverted. This would turn our big blue fish into a small blue fish, since it’s much simpler to determine the opposite of big than blue. If one attribute is not easier to invert than another, then it may be acceptable to invert both or all of the attributes.

But sometimes one of the attributes, though just as significant or even more significant than the others, just doesn’t make sense when inverted alone. So if we had to find the opposite of a generous friend giving money, it wouldn’t be a selfish friend lending money. A generous friend taking money doesn’t make much sense either. It would be best to invert both generous and giving, making this person a selfish friend taking money, which makes a lot more sense.

Some people have difficulty just identifying attributes of a subject, let alone determining which one to invert. This is because attributes are not equal to adjectives. Attributes are features or characteristics of the subject. In the example above, a generous friend giving money, generous is obviously one of the attributes of friend, but what about giving money? The term giving is not an attribute on its own, and neither is money, for if we separate them, then there are two subjects: friend and money. No, in this case giving money is the second attribute of friend, because we all know that the opposite of giving money is taking money, not taking non-money. In a way, each attribute is treated as its own separate opposite before being tested against any other attributes and then applied to the original subject.

The only other obstacle that runs this theory ashore is a subject with no describing attributes. In these cases, we can defer to opposite subject theory, since that is the only remaining solution. Now let’s see how it works.

| Original |

Opposite(s) |

Explanation |

| A Chicken |

An Egg |

|

|

No attributes, invert subject. Chicken and egg are binary opposites. |

| Sea |

Land |

Sky |

|

No attributes, invert subject. Sea, land and sky are binary opposites. |

| A Giant Chicken |

A Tiny Chicken |

|

|

Giant and tiny are polar opposites. |

| A Skilled Carpenter |

A Clumsy Carpenter |

|

|

Skilled and clumsy are polar opposites. |

| An Emotional Romance Movie |

A Dull Romance Movie |

|

|

Cumulative adjectives. Emotional is easier to invert than romance. |

| A Beautiful, New House |

An Ugly, New House |

A Beautiful, Old House |

An Ugly, Old House |

Coordinate (independent) adjectives. No primary attribute. |

| A Shy Girl on a Blind Date |

An Outgoing Girl on a Blind Date |

|

|

Shy is the primary attribute. Shy is easier to invert than on a blind date. |

| A Horrible Disease That Kills Quickly |

A Horrible Disease That Kills Slowly |

|

|

Horrible is the primary attribute, but inverting it doesn’t make sense. |

| A Strong, Handsome Hero |

A Weak, Hideous Hero |

A Strong, Hideous Hero |

A Weak, Hideous Hero |

Coordinate (independent) adjectives. No primary attribute. |

| An Honest Lawyer Telling the Truth |

A Dishonest Lawyer Telling Lies |

|

|

Honest is the primary attribute, but inverting it alone doesn’t make sense. |

As we can see, the answer largely depends on context. It seems strange that the opposite of a chicken is an egg while the opposite of a giant chicken isn’t a giant egg. However, if our attribute was friendly, rather than giant, then it would seem silly to invert the subject, since eggs are hardly friendly at all.

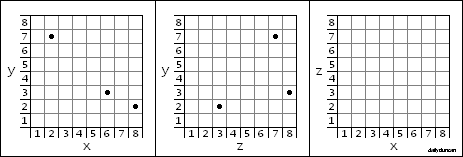

Likewise, it would appear to many that the opposite of a strong, handsome hero must be a villain, since they could be considered both polar and binary opposites. But again, inverting the subject is only tempting in these situations because there is an obvious opposite to the subject. If it was a Russian farmer who was strong and handsome, then we would be much less inclined to find the subject’s opposite. As a final example of opposites, let’s consider the case of one of the most popular comic book heroes of all time: Superman.

Superman has faced many foes over the years, including cyborgs, monkeys, millionaires, thieves, ghosts, gods, demons, environmentalists, Kryptonians, scientists, magicians, aliens and many others. Although Superman has handled a wide variety of villains, some of them are more memorable than others. This is because a good villain is the antithesis of the hero, standing against what the hero stands for and embodying virtues that oppose those of the hero. Most heroes have an archenemy or nemesis, which is usually a being who is their perfect opposite.

Although many would identify Lex Luthor as Superman’s nemesis, there have been several attempts to create an evil counterpart to the Man of Steel. Ultra-Humanite, Lex Luthor, Ultraman and Bizarro were all made with the intent of producing a villain who is completely contrary to Superman, but did any of them really succeed?

These four foes basically fall into two categories: the ones with superpowers and the ones without. Ultraman and Bizarro have similar or identical physical powers to those of Superman, such as flight and super-strength, while Ultra-Humanite and Lex Luthor have only increased intellectual abilities. Ultra-Humanite even possesses a crippled body, which was meant to make him a more complete opposite of Superman.

Also, in Kill Bill: Vol. 2, David Carradine’s character argues that the antithesis of Superman is actually Clark Kent – a cowardly, benign human with no interest in helping or hurting others. So which one of these characters is the true opposite of Superman? Let’s take a look at each of them and see whether they are using polar or binary opposites and which opposite theories are being applied.

| Character |

Features |

| Strength |

Intelligence |

Super Powers |

Personality |

| Superman |

Super |

Normal |

Flight, Heat Vision, Freeze Breath, etc. |

Selfless, Humble, Honest |

| Ultra-Humanite |

Limited |

Super |

None |

Selfish, Insane, Hateful |

| Lex Luthor |

Normal |

Super |

None |

Selfish, Ambitious, Deceitful |

| Ultraman |

Super |

Normal |

Flight, Heat Vision, Freeze Breath, etc. |

Selfish, Ambitious, Deceitful |

| Bizarro |

Super |

Limited |

Flight, Freeze Vision, Flame Breath, etc. |

Confused |

| Clark Kent |

Normal |

Normal |

None |

Disengaged, Timid, Fearful |

As we can see, each villain has its own approach to opposing Superman’s features. Ultra-Humanite and Lex Luthor mirror Superman’s incredible physical abilities with intellectual abilities, since they are binary opposites, with Ultra-Humanite’s inferior physical strength representing a polar opposite. In the same way, Bizarro’s limited intelligence is an attempt to mirror Superman’s normal intelligence, though also serving to separate him from other villains. Instead of contrasting Superman’s physical abilities, Ultraman and Bizarro share Superman’s powers, but some of Bizarro’s abilities are actually inverted from those of Superman.

As far as personality and behavior goes, Bizarro again separates himself from the pack with a lack of obvious maniacal intent. Superman is good, and the opposite of good is evil, so it would make sense to have an evil nemesis. But Bizarro, like the other villains, is a combination of opposite types and theories, so it’s likely that his creators were merely attempting to make a character who was extremely dissimilar to Superman in all respects. Unfortunately this doesn’t explain why Bizarro flies instead of digging and why he isn’t physically weak like other villains.

Clark Kent, on the other hand, embodies not the opposite of Superman’s features, but the absence of them. And, as we already discussed earlier, the opposite of something is not nothing. If Clark Kent was the opposite of Superman, then he would also be the opposite of Lex Luthor, Bizzaro and any other extraordinary character.

Of all of Superman’s Enemies, Bizarro is the most obvious attempt to create a complete opposite. Bizarro’s creators even went to so far as to give him the ability to see a short distance behind his head, which is supposed to be the opposite of Superman’s ability to see a great distance in front of him. Although they obviously went to great length to ensure that Bizarro was the complete opposite of Superman, they ultimately failed. This is because there can be no true complete opposite of something with as many characteristics as a person, especially when we know so much about them.

Superman is not just a Superhero with superpowers, he’s an alien, an idealist, a person of moderate height and intelligence, he’s brave, friendly, helpful and good-looking, he has short, dark hair, he’s not an amputee or a football player, he never gets sick, he can see, smell, taste, touch and hear, he’s emotionally stable, he sleeps in a bed and so on.

This is why complete opposite theory and opposite attribute theory can’t work: there are too many characteristics to invert. As we already discussed, the best way to find the opposite of something is to invert its primary attribute or attributes, so we need to ask ourselves what are the most defining features?

Well, since Superman is the only Kryptonian on Earth, that would be a good place to start. He also possesses incredible physical powers that other people do not, and he’s a hero who has dedicated himself to defending Earth and its inhabitants from evil. What’s the opposite of a physically powerful alien selflessly protecting others? Probably an intellectually powerful human selfishly exploiting others.