In life there is great uncertainty. Humans are constantly seeking explanations and crafting theories, struggling to decipher what is meaningless and categorize what is random. This urge to eradicate uncertainty gives rise to superstitions, rituals and maxims. We crave a fixed framework which correlates our behavior with our experience. More often than not, no such correlation exists, but that doesn’t stop us from trying.

In primitive cultures, the harvest of creatures and crops is a matter of survival. Because of the paramount importance and unpredictable nature of these harvests, members go to great length to ensure a bountiful yield. Sacrifice, worship, and ritual are common practices aimed at inducing a favorable outcome. Despite their lack of empirical support, these rituals are often based on inductive reasoning. Imagine, for example, a hunter, before setting out in search of prey, kneels down and rubs dirt on his hands. After having a successful hunt, a correlation is made between the behavior and the result and a ritual is born.

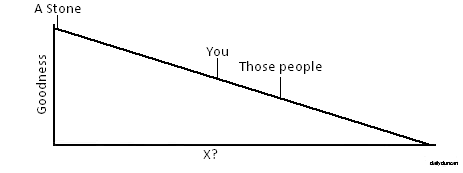

Though we have shed our primal roots, we still operate with an expectation that certain behavior will produce certain results. Slogans such as, “you reap what you sow,” and, “the early bird catches the worm” represent the common association of hard work and fiscal gain. Although these slogans may define a general pattern, as guiding principles they are as reliable as a rain dance or animal sacrifice. There are many notorious quotes by renowned thinkers which describe these patterns, yet they all fall distinctly short of absolute credibility. Sometimes the diligent are punished while the lazy are rewarded. Sometimes the deceitful are praised while the honest are ostracized.

One avenue to certainty is statistical probability. Instead of attempting to mold rigid models to predict results, we can rely on the malleable and empirical nature of probability. Although this method has great value in certain areas, it does not satisfy our craving. Knowing that honesty is the best policy 57% of the time does not inspire honesty.

Though correlation and reasoning may not produce stable hypotheses, there are other tools which can be used to provide certainty. Mathematics is a field in which certainty is abundant; every equation has one result, one solution. In math, there is no interpretation, no ambiguity and no subjectivity. Unfortunately, mathematics does not correspond to our experience, but his cousin, physics, can be more helpful.

Everywhere we look, we can find patterns and trends in the universe. Truth can be found in the gravity of a black hole and the structure of an atom. The concept that no two things are identical is an example of extracting truth by observing our physical world. This idea reminds us that we should never treat two people or situations the same way. There is another principle which we can pry from the laws of the universe, one which can teach us a great deal about life, death and morality. This concept is known as the Zero One Infinity Theory.

The theory describes how objects and events of significance only manifest in one of three ways:

- The object or event has never existed and will never exist in the future.

- The object or event will only exist once, or under one condition, for a finite length of time.

- The object or event has always existed and will exist for all of time.

From this theory we can learn many things, let’s look at two examples. First, that cosmic and spiritual objects and events must exist in one of the three forms. For example, there is either no such thing as reincarnation, one reincarnation (or under one condition), or eternal reincarnation. The same rule applies to the number of inhabited planets, best men, deities and universes. One need not know a great deal about physics to realize that it does not make sense to only two universes in existence.

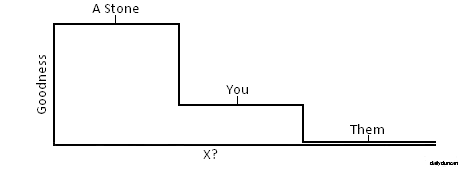

The second thing we can learn is that moral behavior in our lives should exist in one of the three forms. For example, we should either never tell the truth, tell the truth under only one condition, or always tell the truth. This also applies to things like theft, divorce, drug use, abortion and eating animals. All significant human behavior should be forbidden, permitted or required under one condition, or always permitted or required. Applying this pattern to our moral code will chisel the surface of the slope of judgement into the rigid and defined steps of judgment.

Some argue that a fourth option should be instated, that two is a legitimate number of occurrences. Though their thoughts are pure, these poor people are mistaken. Any amount of occurrences or exceptions beyond the first is arbitrary and shall be relinquished to the hands of infinity. Humans attach significance to many numbers for many reasons. We might value two because most external body parts appear in pairs, or because relationships require two people, we value three because three points are required to draw an enclosed shape and we value ten because of the decimal system. Regardless of the reasoning, these supposedly sacred numbers are generated by humans, who cannot be trusted in such matters. Principles of this magnitude must exist beyond humanity, uncorrupted by our interpretation. Though the number two may its own significance, you cannot have two universes or two gods. As Isaac Asimov stated, “Two is an impossible number, and can’t exist.”