Yesterday you woke up from your bed and dressed yourself for the day. In addition to accomplishing the day’s necessary tasks, you ate some food and enjoyed leisure time, possibly with friends or family.

When you woke this morning, you dressed yourself in different clothes, and after accomplishing your daily tasks, ate different food and spent your leisure time in a different way, likely with different people. Why the change? Why didn’t you wear the same clothes, eat the same food and relax the same way as yesterday? Your clothes are still in style, the food tastes the same and your friends and activities are just as interesting. The answer is actually woven into the very nature of the universe: the inevitability of change.

At some point in the distant future, gravity will condense all matter in existence into a singularity. This is likely the end of the universe, after which there will be no more change. But until entropy finally conquers the universe, collapsing all matter and dissipating all energy, everything must always be changing. Particles collide and energy transfers as stars and planets dance and scatter light through space.

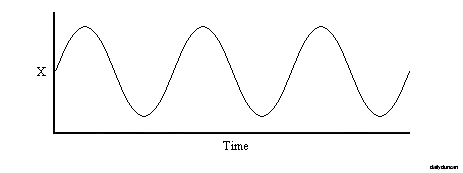

Inside the fabric of reality, beneath our subconscious and between the helices of our DNA is the necessity for change. We battle against entropy, attempting to minimize the chaotic nature of universe, but we can’t truly escape it. It’s impossible for anything to remain truly constant, but the closest thing to constant is undulation, and that is what we experience: the sine wave of life.

X can be anything from happiness to hunger, sleepiness to sexual desire, even wealth, fashion, friendship or conflict. The undulation describes each individual, family, city or nation, and it’s accurate on a variety of time scales. It describes our days, weeks, years, lifetime or even our entire history. Here are some common places in which the wave’s undulations can be witnessed:

- A person observed daily: sleep, bathe, get dressed, work, eat, relax, sleep.

- A student observed during a semester: enroll, learn, study, write exams, vacation, enroll.

- A lineage observed during a lifetime: birth, adolescence, adulthood, old age, death, birth.

- A constituency observed through a term of office: elect, celebrate, complain, yearn for change, elect.

Obviously the highs and lows are not always equal, and the undulations are not uniform in length. Sometimes we will experience terrible tragedy or great joy, creating an unusually intense wave. There are also periods of dullness or inactivity, both large and small, in which the waves are so tiny and so fast they could hardly be said to have occurred at all. But this steady undulation is generally accurate and does provide a unique view of our existence.

Now it’s true that all things come to an end, so the undulation cannot continue indefinitely. Some argue that after the end of the universe, another big bang will occur and create a new universe, but this idea is based almost entirely on wishful thinking and a poor understanding of the origin of the universe. Regardless, the undulation must eventually end, and we already know how this will end: the same way it began.

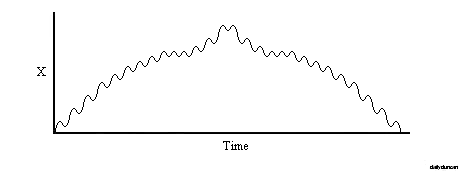

The lifespan of any system, entity, event or organization tends to start with a dramatic rise, experience an apex near the center, then decline sharply toward the end. So if we were to zoom out from the sine wave and observe the subject from beginning to end, we would see that the wave is actually part of a much larger parabolic arch.

An example of this parabolic effect would be the sharp rise and eventual decay of satisfaction while eating a meal, or the initial excitement and appreciation for a new vocation, which eventually fades into boredom, apathy and finally termination.

If we zoom in on any sine wave, we can see that there are even smaller undulations that occur during the larger ones, for each experience or undulation is comprised of an infinite number of smaller events, right down to the subatomic level.

These waves reflect the less significant fluctuations that occur throughout an experience. Here are some examples:

- A mouth observed during a meal: bite, chew, swallow, drink, wipe, bite.

- A student observed during a study session: focus, read, get distracted, take a break, focus.

- A mother observed during childbirth: push, wonder when it’s over, breathe, push.

- A politician observed during a campaign: do an interview, give a speech, shake hands, kiss a baby, travel, do an interview.

As individuals, much of our time and energy is dedicated to the satisfaction of temporary urges – urges that return again and again. Most of us derive a great deal of satisfaction from appeasing these requirements, and some even extract meaning and identity through this process. After all, without constant cravings for food, sleep, sex, fun and friends, how would we spend our time?

Lack of appetite for food, sex and social interaction is often a sign of illness, for no healthy person would choose to avoid these things. But if there was a procedure that eliminated these urges without compromising health, such as a pill that eliminated the need for sleep, it’s likely that few would be frantic to sign up.

There are those who would describe this view of existence as nihilistic or depressing and argue that there are more noble aims, such as helping those in need. But is helping others not simply assisting them in satisfying their own temporary cravings? By devoting ourselves to feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, befriending the lonely or eliminating disease, we are affirming the paramount importance of food, clothing, friends or health. And while we may improve quality of life, the formerly in need are not exempt from the undulations of life and its inevitable parabolic end.

Those who preach salvation would likely contend that the true purpose of life is not found in the satisfaction of needs (or even the needs of others), but in the glorification of a deity and eventual perfection of existence in the afterlife. But glorifying a deity is merely providing satisfaction to a being that craves glory, and most religions promise an afterlife that fulfills our needs and desires with feasts, kingdoms, virgins and gold. And if heaven is merely dedicated to the eternal gratification of a deity and of our own Earthly appetite, does this not mean that we, like our deities, are destined to be eternal consumers?