Uncertainty about the future is something that plagues us all. Indeed, in every civilization throughout history there have been those who claim to have special insight into events that have yet to unfold. In our eagerness to rid ourselves of our fears, we often reward these people handsomely for their supposed knowledge.

Although astrology and mediumship are still popular in Western culture, a more modern profession of precognition has recently arisen: the futurist. Rather than observing heavenly bodies or communicating with spirits to obtain special knowledge, a futurist uses their knowledge and expertise in a given field to predict the future. One of the most well-known of this new breed of fortune teller is Ray Kurzweil, and he’s made a number of shocking predictions about the future of technology and ascension of artificial intelligence. While his claims have brought him great fame and profit, he’s certainly no prophet.

The fact that he doesn’t deserve the label of prophet is not a commentary of the accuracy of Kurzweil’s predictions, though they are certainly worthy of suspicion, but rather an important distinction about the method by which his knowledge is attained. A prophet is someone who communicates a message on behalf of a divine or supernatural source. While Kurzweil’s predictions are certainly otherworldly, they are not the result of divine inspiration or supernatural powers (as far as we know).

Another difference is that prophets usually do not benefit from their insight, but freely offer their knowledge to help others, usually in response to a divine command. Without getting too deep into the issue of discerning the authenticity of a prophecy, we can probably assume that the presence of praise and reward is probably a strong indication of a false prophet. Now let’s take a closer look at prophecies and what it means to be a prophet.

Nostradamus is one of the most popular of those who claimed to predict the future. Born in 16th century France, he produced thousands of predictions. Some of these were accurate, some inaccurate but most are too vague to determine their meaning. Consider Nostradamus’ quatrain #1-35:

The young lion, shall overcome the older

On the field of battle, by singular duel;

Through armor of gold, his eye will be pierced,

Two wounds in one, then to die a cruel death.

Those who believe in Nostradamus’ abilities claim that this verse describes the accidental death of King Henry II of France during a jousting tournament. Followers also claim that Nostradamus predicted the rule of Hitler, the September 11 attacks, the conquest of Napoleon, the Kennedy assassinations and many other major events. However, even if we can determine with certainty that the predictions are referring to these historical events, of what use are they? After all, the events still happened. And if we’re only able to associate a prediction with an event after the event unfolds, then it serves no purpose other than to astonish.

Nostradamus admitted that he wasn’t a prophet, and he based his predictions on a number of sources, including astrology, Biblical text and other works of prognostication. He also didn’t meet the requirement that he help others with his clairvoyance. This doesn’t mean that Nostradamus meant harm or didn’t care about others. Perhaps he meant well, but without specific instruction on how to respond to a prediction, it is impossible to help. And if he actually could predict the future, Nostradamus would have known that his predictions wouldn’t change anything. A true prophecy is meant to be understood before it unfolds, and it includes a response. This leads us to our next point: the purpose of a prophecy.

Aside form their divine or supernatural origin, prophecies tend to function as warnings, usually warnings of catastrophe. Astrologers, mediums and futurists tend to focus on the positive. After all, who would pay for a prediction that makes them upset? On the other hand, just because a prophecy warns us of a threat does not guarantee that it is authentic. There have been plenty of false prophecies about the end of the world, including the famous Mayan apocalypse, which was supposed to occur in 2012. With all of these predictions of the end of the world, it seems that we can be certain of one thing:

“No one knows the day or hour when these things will happen…” (Matthew 24:36)

Another trait of a prophecy is that it is specific. As we mentioned earlier, a vague prediction is of no use to anyone. While it’s easy to make ambiguous statements about lions, wounds and golden armor, it also draws much less attention than a claim about the day the world will end. The specificity of a prediction is usually also proportional to the number of predictions made, offering a choice between quality and quantity. In addition to being extremely specific, a prophecy usually contains only a single prediction.

In summary, here are the defining characteristics of a prophecy:

- Its origin is divine or supernatural, not based on mere observations.

- It doesn’t benefit the prophet.

- It is understood before it unfolds.

- It warns of a catastrophe and includes a call to respond.

- It’s very specific and usually contains a single prediction.

Alright, so now we can identify a prophecy from a prediction, but predictions actually come in many shapes and sizes. Every day we ask meteorologists to make a prediction about the weather, and it’s a relatively easy one to make. This is because of the high availability of information about coming trends and the fact that there are only a limited number of possibilities. It’s also easier to predict something that’s closer to the present, which is why a weather forecast rarely reaches beyond a week or two.

The biggest tool for predicting the future is examining the past, or more accurately, comparing the past to the present. If we can find a recurring trend in the past and identify where we are in the trend, then we can theoretically predict what will happen next. Economists use this tactic to predict booms and busts. Here’s an example:

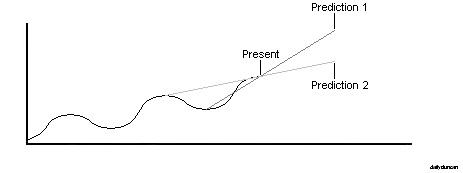

From our position in the present, we can use a number of different strategies to make our prediction. We can look back at a recent significant event, and use that to make our guess:

Or we can look at a recent or ancient measurement:

There are still other strategies to employ. We could take a number of measurements and average them, or we could try to find an algorithm that describes the occurrence of booms and busts. We could even ignore all past information and consider only current trends. Part of the reason why the predictions of futurists like Kurzweil are so extreme is that there isn’t a lot of past information on modern technology. There’s only been one computer age, one Internet and one Google, so it’s hard to say where we’re headed.

One of the great predictions of the 20th century was made by Gordon Moore in 1975. He observed that transistor density on integrated circuits was increasing at a steady rate, so he predicted that the transistors count would continue to double every two years. This prediction has largely proven accurate, though some say this is merely because the semiconductor industry uses it to set research and development targets.

However, even a prediction heralded for its longevity and accuracy hasn’t yet outlived its maker and may soon be proven irrelevant. The capacity to build smaller transistors will eventually end as they approach the atomic scale. In addition, quantum technology threatens to shatter the entire framework of computing architecture. Overall, the rapid change in technology makes it an exceedingly difficult subject to forecast.

If we take a look back at films that depict the future (our present), we scoff at their interpretations. Decades later, the flying cars, jet packs, food capsules, laser guns, tiny cellphones and robot dogs we saw on the big screen are nowhere to be found. Part of the reason for this folly is the inclination to imagine improved versions of things we already use, essentially futurizing things found in the present. This is because our imagination is largely limited by what we’ve already seen.

Visionaries like Gene Roddenberry were able to imagine a future quite different from our own, with inventions that weren’t just improvements, but whole new concepts never before seen or imagined. Yet even Roddenberry could not predict some of the advances in technology we see today. Although we may not have yet conquered poverty, disease or intergalactic travel, things we do every day on our smartphones were beyond his comprehension.

Another factor that makes prediction difficult is the chance of catastrophe. It’s possible that we establish a colony on Mars in the next 50 years, but it’s also possible that a massive earthquake hits Washington, D.C. and levels NASA headquarters. The problem with catastrophes is that we can’t be sure when, where or how they will happen, just that they will happen.

By contrast, there are also trends that come and go, cultural shifts brought on by subtle and gradual changes to our collective psyche. If we could turn back the clock to July 21, 1969, we likely couldn’t find anyone who would predict that we wouldn’t visit any other planets in the next 50 years, yet here we are still stuck on this boring old dust bowl. The lunar landing ignited imaginations and had a huge impact on television and film, but our interest in outer space fizzled. Likewise, virtual reality was a huge trend in the 1980s, but is only new seeing a resurgence 30 years later.

We also make a huge error when we consider the advances that humans have made in recent years and assume that everyone has experienced these improvements and that there have been no consequences. Billions of people across the globe have yet to experience sanitation and safe drinking water, which makes the whole futurist thing seem kind of vain and meaningless. We also tend to think of technology as the solution to the world’s problems, ignoring the huge environmental cost and health hazard of manufacturing integrated circuits and other electronic components. We like to think that we’re on a trajectory toward perfection, but in many ways we’re worse off than we’ve ever been. Here are just a few examples:

- Obesity is a global health crisis.

- Voter turnout continues to fall.

- Education is failing our youth.

- Social media, video game and pornography addiction are increasing.

- We’re consuming and corrupting the Earth’s resources at an unsustainable rate.

- The gap between the rich and poor is growing.

- Depression and anxiety are on the rise.

- More children are being raised without both parents.

- Large sections of the population have no legal protection.

- The government has alarming levels of surveillance on its citizens.

- Sexual promiscuity among adolescents is increasing.

Of course, it’s not all doom and gloom. War, poverty, and disease are on the decline (in most places). The point here is merely that the world is a big, complicated place, and that it’s easy to believe that everyone’s lives are as good as ours and get caught up in the excitement for what’s ahead. The world is getting better, but not for everyone and not in every way.

So what’s the future going to be like? Well it’s probably going to be similar to the present. Despite all of the advances in technology and the social, political and economic change, we still get up, go to work, pay our rent, cook our food and so on. But predicting that things will generally stay the same is not interesting or provocative. If we want people to heed our warning or buy our book, then we have to predict something that grabs headlines. Let’s take a stab at creating our own prediction. Here’s how we do it:

First we need to make sure that people pay attention to us, so we should probably choose a subject that is interesting, relevant (or seemingly so), and a little controversial. How about the Internet?

Next we need to choose a timeline. We need to pick a date that is close enough to seem meaningful, but distant enough that we can’t be proven wrong anytime soon. Choosing a point too far in the future also makes our prediction seem less credible, since we have to provide a basis for our forecast. We should also choose a number that seems significant. Let’s go with 20 years.

As for actual the prediction itself, we merely need to spot a trend, then choose a point in recent history and extrapolate a seemingly-reasonable projection into the future. Access to the Internet is on the rise, so let’s predict that in the next 20 years everyone on the planet will be online. Now we just need to find some numbers to back it up.

| Year | Population (m) | Users (m) | Users (%) | Increase (m) | Increase (%) |

| 2005 | 6514 | 1024 | 15.72 | – | – |

| 2006 | 6593 | 1151 | 17.46 | 127 | 1.74 |

| 2007 | 6673 | 1365 | 20.46 | 214 | 3.00 |

| 2008 | 6753 | 1561 | 23.12 | 196 | 2.66 |

| 2009 | 6834 | 1751 | 25.62 | 190 | 2.51 |

| 2010 | 6916 | 2019 | 29.19 | 268 | 3.57 |

| 2011 | 6997 | 2224 | 31.79 | 205 | 2.59 |

| 2012 | 7080 | 2494 | 35.23 | 270 | 3.44 |

| 2013 | 7162 | 2705 | 37.77 | 211 | 2.54 |

| 2014 | 7243 | 2937 | 40.55 | 232 | 2.78 |

| 2015 | 7324 | 3174 | 43.34 | 237 | 2.79 |

Pulling up some figures on global population and Internet access, we can clearly see that the number of people online is rapidly increasing. In the past 10 years, we’ve seen it jump from around 15 per cent of the world’s population to over 43 per cent, so it’s definitely believable.

Now we should think about the specificity of our prediction. It shouldn’t be so vague that it is indecipherable, but it also shouldn’t be so specific that people can agree on its meaning and critique it. We also want to leave room for reinterpretation, should things take an unexpected turn. For these reasons it’s important to choose our phrasing very carefully.

Let’s go with this: all people will have access to an Internet connection in the next 20 years.

We use all people instead of everyone because it could refer to groups as well as individuals. We also say have access to an Internet connection, not be connected or have Internet access, because it’s more broad. After all, anyone with the potential to have electricity and a satellite dish is already included. We also say in the next 20 years instead of by 2035 because the year 2035 seems like it’s further away.

And there we have our prediction. Now we just need to give ourselves a fancy title that doesn’t require any credentials, like futurist or technology expert, and we’re on our way to fame and fortune.