In part I we learned about the relationship between humans and artificial beings, such as androids and toasters. We also learned about the plight of such beings which are too human to be treated like a robot, but too robotic to be human. Unfortunately, robots are not the only creatures trapped at the depths of the uncanny.

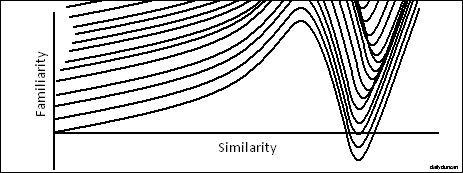

The graph we looked at in Part I was merely a two dimensional interpretation of a larger concept: the Uncanny Canyon.

Each line, or valley, is a representation of only one variety of the condemned. The canyon depicts the rejection, by humans, of the uncanny – that which closely resembles the familiar, but is not familiar. When we encounter something that is ordinary, yet strange, we can experience cognitive dissonance, resulting in the abjection of that uncanny thing. Basically, we reject that which imitates, or resembles, what we know and love. Anything which rings the bells of familiarity, yet is foreign to us, is a counterfeit and is treated with suspicion, including other people.

Whether we live in a multicultural or agricultural society, we find ways to separate ourselves from others and define our identity. Our clothes, speech, diet, musical taste and preferred sport – we use them all to distinguish ourselves as individuals. However, there is more to identity than individuality, for humans also have a desire to belong. We find others who share our behavior and preference, uniting with them to define our social identity.

Many wars which may appear to have been fought over money, power or religion, were actually fought over identity. In order to have a war, or any conflict, we must have an us and a them, and this distinction is most often made over small differences. If there was no identity, there would be no conflict in the world, but, whether by primal instinct or social convention, identity has become essential. This is why we are suspicious of others who resemble ourselves; they are a threat to our identity. Let’s look at some situations, both historical and ongoing, in which sharing similar behavior, origin and preference has led to rejection and conflict.

- Schoolyard rivalries

- Horde vs. Alliance

- The Rwandan Genocide

- Nintento vs. Sega

- Protestants vs. Catholics

- Mac vs. PC

In all of these examples the two sides share far more in common with each other than they share with any other group. PC users and Mac users may seem drastically dissimilar, sharing no more in common than John Hodgman does with Justin Long, but they actually only disagree on minor differences in user interface. Because the two sides share so much in common, they take intentional measures to segregate themselves from each other by creating unique vocabulary and launching ad campaigns.

High school is a breeding ground for us vs. them behavior. Even though the students may all be of similar age, live in the same area, have the same teachers and attend same classes, they are compulsed to separate themselves from each other, banding into rivalrous factions.

Without similarity, there is no conflict, for those who are vastly different from us cause only curiosity, not contempt. The reason for this conflict is because these groups have enough in common to make them suspicious of each other, but not enough to unite them, for unity is a part of human nature, but unity only with those who have crossed the Uncanny Canyon.