In part I we discussed the different forms of competition, the origin of sport and the difference between direct and indirect competition. Now we will explore the role of competition in other areas and determine whether it’s actually a constructive behavior.

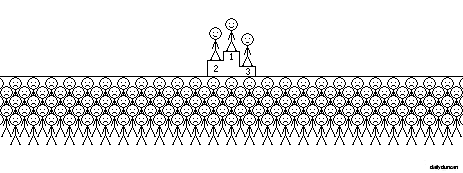

As we discussed earlier, the major function of competition in nature is to ensure the survival of those most fit for their environment. Modern human competition is used to propel ourselves to achieve new levels of excellence and elevate those who are more talented or dedicated. Competition is a wonderful thing for those who succeed, but as Charles Schulz reminds us, “Nobody remembers who came in second.”

Beyond the podium, in silent locker rooms and on long drives home, the unremembered contemplate the purpose of their efforts. Failure is a necessary component in competition; there’s no way round it. Even the most innocent and well-meaning contests produce failure. These failures are not incidental, but a requirement in order to produce the successes, for a competition without losers is not considered legitimate.

By asking individuals to compete against each other, we are demanding failure. We’re taking pleasure in watching people devote their lives to something and come up short. This reveals how competition is actually a cruel experiment carried out by fans, coaches and parents. By enticing individuals with visions of fame and fortune, while planting false ideas of superiority and a right to win, competitors are conduced to compete, and often fail, for our amusement. But when disappointment falls on those who didn’t achieve their goal, their only consolation is that they may have a chance to redeem themselves. This cycle can continue indefinitely, when a simple cost-benefit analysis of would easily determine that competition is a poor investment.

We may attempt to excuse ourselves from responsibility by proposing that failure is a result of inadequacy, but the fact is that it will come to most, regardless of their efforts. In addition, competition has no sense of justice, so there is no guarantee that the most deserving will be victorious.

Another fundamental part of competition is enmity. Competition is conflict, and in order to have conflict, we must have an us and a them. It is essential that we detach ourselves from those we compete against, for our actions may directly result in their failure. Some competitors intentionally disassociate themselves with their competitors or even foster feelings of hatred in order to compete more intensely or without the restrictions that come with viewing an opponent as a fellow human being. Although there can be great respect between opponents, this relationship is hardly worthy of admiration. There cannot be unity between competitors, for in striving for the same goal we are actually stealing from others what they do not yet possess. There is a limited number of awards to be won, so the aim of each participant is to look out only for themselves, even at the cost of others. This may not be considered theft in the conventional way, but it is by our actions that our opponents are robbed of their prize.

This is also true in the world of business. Looking through the lens of nature, if sport is a dramatization of survival, then economic competition is an embodiment of the battle to feed. Much like blind pups suckling for sustenance, or wild dogs clashing for a piece of a kill, businesses compete to get a larger share of the market. Unlike in many sports, the aim of business competitors is not necessarily the elimination of their opponents, though that is sometimes the case. However, since they are often striving for the same goal, the competition can still be extremely fierce.

Because of the influence of capitalism and our confidence in the competitive market, the competition between businesses seems like an acceptable and upright practice, but the truth of the matter is that many honest, hardworking individuals are regularly driven into poverty. There is no room for empathy in competition, and as we already touched on, no role for justice, since there is no assurance that honest efforts will be rewarded or that underhanded deeds will be punished.

Another example of human competition can be seen in struggle for social superiority. Individuals compete to be the most popular and well-liked because we derive value from the knowledge of how we are perceived by others. This motivates us to keep up with, or surpass, those around us in whatever categories we deem important. Whether it be a measure of wealth, beauty or accomplishment, we can’t help but create competition with those around us.

Unlike official contests, these social arms races are conducted in silence, without terms or rules, and they are eternal. There is no beginning or end and no declaration of winners or losers in social competition, only the vague sense of comfort and supremacy that comes with being better at life than others. Social competition is indirect, since we rarely interfere with others’ quest for material excellence, but the frustration and sadness of those trapped below are definitely real. When we show off our new house, toned figure or gold medal to our neighbor, we could be subjecting them to feelings of inferiority, whether or not we are aware that we are competing.

Shall we continue to raise our children to view other people as enemies, to prioritize themselves above others and to subject themselves to failure for our amusement? Shall we chase success at the cost of the misery and failure of others, like ravenous beasts?