Many parents enroll their children in musical instrument lessons at an early age in hopes of fostering discipline, focus and an affinity for music. What they don’t realize is that focus and discipline aren’t cool. What’s cool is playing the guitar, and most parents make their kids learn some culturally irrelevant instrument like the harp or piano.

If you were one of those unfortunate children, then you were likely filled with poisonous envy every time you saw someone serenade their peers with a simple tune from their guitar. You also harbored secret resentment toward your parents, who didn’t have the foresight to choose an instrument that would make you popular.

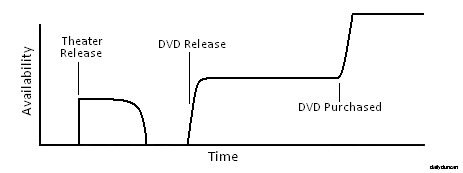

The most common choice of instrument for children by their parents is the piano. This is likely because pianos add a subtle elegance to the living room and they can be played at a mild volume. But children don’t want to play the piano. All of their favorite musicians play the guitar, and keyboard players in most bands are easily and frequently replaced. This is why, as teenagers, many piano students eventually attempt to learn the guitar. However, there is a great hurdle that students of the piano need to overcome when learning the guitar: guitars don’t make sense.

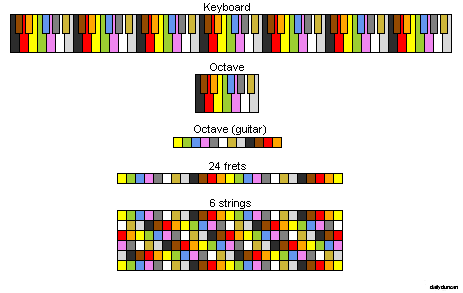

If you are one whose first language is the piano, then you probably have a difficult time understanding how the guitar works. This is because a piano’s keys are is simple to play and its notes are arranged in a linear progression; the guitar is much different. This is how a piano player sees a guitar:

This example uses standard tuning on a six-string guitar with twenty-four frets. The guitar’s notes are a maze compared to those of the piano, but this diagram doesn’t tell the whole story.

The use of color in musical notation has long been ignored. By assigning each note in an octave its own color, students can recognize each note much more quickly and easily. This also allows us to more clearly see the drastic dissimilarity between the arrangement of notes on a keyboard and a guitar. For this example we will borrow the electronic color code, since it has twelve colors, and this will promote uniformity between the professions, allowing those in the electronics field to easily transition into music.

Now we’re getting somewhere. Because each string has its own tuning, the colors produce a chaotic spectrum that is sure to confound even the most accomplished pianist. This depiction isn’t entirely accurate, however, since it does not portray the horizontal distance that the guitar’s notes would cover on a piano.

There you have it, a guitar is actually six individually-tuned keyboards stacked one on top of another, offset by several notes. Even if we can make sense of this system, there is still the problem of adapting to the puzzling mechanics of the guitar.

The guitar has a shorter range of frequency than the keyboard. Also, the keyboard can be played with either or both hands, while the guitar must be played with two hands at all times. Both hands operate in basically the same way on a piano, while the guitar requires that each hand perform a distinct function. Furthermore, a keyboard player may strike one to ten different notes at the same time (or more if afflicted by polydactyly), while a guitarist may only pluck one or two strings or strum up to six adjacent strings. Guitar players are also limited by the tuning of the guitar, since each configuration has its own advantages and drawbacks.

One way to avoid some trouble in transitioning from the piano to the guitar is to use open tuning. This guitar configuration allows chords to be played without learning complex fingering.

Although the differences may not appear significant, open tuning produces a major chord when six parallel frets are held together. This allows the musician to play each major chord by simply stretching one finger along a fret.

So you want your children to learn piano? Teach them guitar. Once they can play the guitar, learning the piano will be a breeze.