Some see the world in black and white, others see it as gray. Some believe that every action is either right or wrong, others believe that some, or even many actions, fall somewhere in between. Is one of these perspectives right and the other wrong, or is it a gray area?

If we define a true, right, or correct statement as one that is 100% accurate and always applicable with no exceptions, caveats, generalizations, or oversimplifications, then most statements are false. In fact, it’s likely that all statements written and uttered are false by this standard, including this statement. Let’s look at some age-old adages and see how they measure up:

- It’s better to be safe than sorry.

- Actions speak louder than words.

- The early bird catches the worm.

- Don’t judge a book by its cover.

- Where there’s a will, there’s a way.

- If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

If we ponder these proverbs for a moment, we can quickly decipher the simple and mildly profound principle that’s meant to illuminate our decision-making, but are these statements true? Should we always lean toward safety? Is it always better to be early? Is every desirable outcome achievable? Surely it’s no challenge to imagine some plausible, and even common examples in which these statements are completely misleading or irrelevant.

If you are a racecar driver, then exercising caution at all times will not serve you well. And even in less extreme, hyper-competitive situations, such as pursuing a potential romantic partner, taking a chance is often exactly what is required.

Being early is preferable much of the time, but obviously being too early is inefficient and could even be irritating to others. But even if showing up early to in a specific instance does provide a benefit, can we just assume that there’s nothing better to be done with that time? What if instead of being 20 minutes early to work you could have been 10 minutes early and warmed up your car, stretched, or flossed?

There are many things that are impossible to do, and not just because they are a paradox – like standing and sitting simultaneously – or because they violate the laws of physics – like levitating – but simply because life is hard and we constantly fail. Humans are perpetually making trade-offs because we have limited time, energy, and money, but unlimited desires. And we’re always facing challenges that we simply do not have the skills, patience, or determination to accomplish. For most, we cannot will ourselves to become a chess Grandmaster or a Hollywood celebrity any more than we can will ourselves to levitate.

But this leads an important question, if these statements are not true in the sense that they are 100% accurate at all times, then are they really false? Certainly a statement that is helpful for many people and generally correct most of the time is valuable and shouldn’t branded as wrong and discarded. So how do we categorize such a statement?

It seems like these statements should fall into a category that doesn’t really relate to true or false, right or wrong. They’re pretty accurate under normal circumstances, useful much of the time, and require some wisdom in order to be applied. But this isn’t just true of ancient maxims, it’s also true of many of the statements we make every day. Indeed, whenever you express an opinion, especially a political opinion, chances are you’re saying something that is irrelevant, counterproductive, or destructive in many circumstances. Let’s look at some examples:

- Bullying should never be tolerated.

- Drug use should be illegal.

- The rich should pay more taxes.

- Criminals should go to prison.

- Offensive language should be banned.

- Every human life must be preserved at any cost.

Use your imagination for a moment to think of a situation in which the statement above should not apply. It shouldn’t be difficult to imagine a scenario where making an exception is the right thing to do. Here are some ideas to get the wheels turning:

- What if a student bullies another student by shaming or intimidating them because they’re doing something seriously wrong, like harassing, sabotaging, or plagiarizing another student?

- What if the person using the illegal drug would endure extreme suffering, or even die, if they didn’t use it?

- What if the rich person, unlike their peers, is already paying a majority of their income in taxes?

- What if someone breaks just one extremely old, insignificant, and irrelevant law (as we constantly do)?

- What if someone finds mainstream language, such as vulgar or sacrilegious language, offensive?

- What if saving a human life requires inflicting suffering on many others?

And it’s not just proclamations about society, law, and morality that are often wrong. Even the most commonplace, mundane statements are most certainly untrue. Even something as innocent as expressing the simple thoughts and preferences such as, “I don’t have an addictive personality,” or, “Pepsi is better than Coke,” don’t hold up under even tepid scrutiny. Now that we know that everything we read, hear, write, and say is wrong, let’s look at some other kinds of statements and analyze whether they are true, false, or something else.

In science there are principles, equations, and relationships that are measurable and testable both in theory and in practice. We can use Newton’s physics equations to make predictions about the movement of objects, and then we can test those predictions in the real world. They work. That is, they work under normal circumstances with normal-sized objects moving at normal speed. But if we’re working with a subatomic particle in a sub-zero vacuum moving at nearly the speed of light, Newton’s equations break down. Does this mean Newton’s statements about the mass and velocity of objects aren’t true? How can equations that have proven incredibly reliable and immensely useful for centuries be wrong? Perhaps Newton wasn’t wrong, he was merely mistaken?

And herein lies the problem: right and wrong can mean many things. We say that the statement 2+2 = 4 is right, but we also say that helping those in need is right, that it’s right to signal when we make a turn while driving, and that brushing after every meal is the right thing to do. We say that that the geocentric model of the universe is wrong, but we also say it’s wrong to steal, that it’s wrong to make digital copies of a movie, and that burping out loud in public is wrong. We use these terms to assess whether or not something is technically accurate, morally virtuous, compliant with regulation, or simply a good idea, and that’s a very strange thing indeed.

When someone knocks down a set of dominos and one of them doesn’t fall, we say something went wrong. Nothing immoral took place. Some dominos simply weren’t lined up in exactly the right way, which is an honest mistake that’s very easy to make. But what if a child set up the dominos and they were just learning how to do it? Then we probably wouldn’t even say something went wrong. In fact, we’d congratulate them on their success! But what if someone answers a test question wrong? It’s likely a mistake, just like the domino placement, but it could be immoral if the person didn’t study or intentionally answered it wrong out of spite.

When someone tortures an animal, we say that’s wrong. What we mean in this case isn’t that the person made a mistake, but that they did something immoral. It doesn’t matter if they did a good job torturing the animal, whatever that means, or if they tried their hardest or were very sincere, careful, and deliberate about it. The reason they are wrong is that the action they took is unethical – it’s prohibited by the prevailing moral code. The fact that it’s even possible to use the same word to describe committing such a heinous act as we can to describe filling in the wrong circle on a piece of paper really speaks to the gaping chasm that exists in this area of our language.

When someone purposefully leaves their vehicle in a parking stall longer than the allotted time, we say that’s wrong. But they didn’t make a mistake, and it’s not really an immoral act. Some might say it’s immoral, but if we simply imagine that the person was delayed by an unusually long line at the grocery store, how do we categorize the deed then? It’s a mistake, but it’s not an honest mistake (perhaps the person should have noticed that the grocery store’s parking lot was full) and it has consequences for other people. What we could say it that the act was not a mistake, nor was it immoral, but rather it was an infraction or violation. A rule was broken. This doesn’t imply anything about whether or not he person’s actions were justified or whether or not they deserve a parking ticket. We just say that it’s wrong in the sense that there was a very specific requirement in place – unrelated to the prevailing moral code – and that the requirement was not met.

When someone doesn’t get their oil changed on their car for a very long time, we say that’s wrong. It’s not a mistake, it’s not immoral, it doesn’t break any rules, but it’s still wrong somehow. It certainly has consequences, and it’s certainly frowned upon by many people, including the car’s manufacturer, but no one would say this makes the person who does it a bad person or that they should be punished. This type of action is best described as foolishness. The person did not exercise wisdom, because they made a decision – or series of decisions – which will bring about an outcome that they do not want to occur. In a sense, they reaped the benefits when they weren’t prepared to pay the cost.

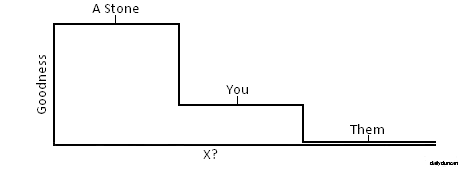

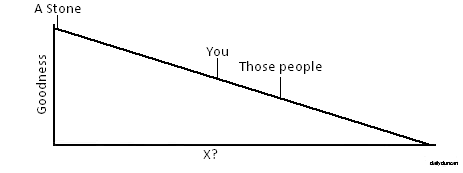

Stay tuned for Part II, in which we will discuss subcategories and degrees of wrongness, and we’ll also find out why everyone you know is wrong about everything.