To begin, answer these two questions:

1. Of the movies you own, which one is your favorite?

2. When was the last time you watched it?

Chances are you haven’t sat down and soaked in this classic in quite some time. You adore this film and you have access to it at all times, yet you never watch it. Why is this?

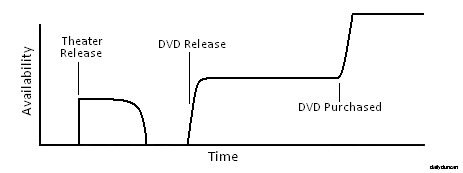

The graph above shows how likely we are to watch the movies that we love during the various phases of release. We can see how excitement and anticipation cause increased viewing likelihood during theatrical and DVD release, as well as small swells upon television premier and DVD purchase. Now let’s see what availability looks like throughout the release period:

If we compare these two graphs, we can see that there is a correlation between the film’s availability and the likelihood of watching it. When the movie is in stages of high availability, the likelihood of watching is increased. This is generally true up to the DVD purchase, when likelihood and availability diverge. What is especially fascinating, and the subject of our focus, is how the likelihood of watching is at its lowest point when availability is at its highest. To clarify: when you own something, you no longer desire it.

Think about all that you desire in life. These are things that you do not currently have. At first it seems obvious and appropriate that we do not yearn for something which we possess, but this behavior is, in fact, strangely self-defeating and masochistic.

Besides possession, or ownership, and desire, choice also contributes to the behavior. In order to desire something, there must be an option for us to desire (choice).

As we can see above, when there is no choice, there is no desire, for we are forced to accept out situation. When we have choice, desire flourishes, for we can then desire all the things that we do not have. When there is an oversaturation of choice, we have no desire; this is sometimes called choice fatigue. For example, let’s say that you just bought a brand new television, but it’s 1960 and you only have 7 channels. Because there are so few channels, and no option of acquiring more, you are forced to enjoy those 7 channels thoroughly. As a contrasting example, imagine you recently subscribed to satellite television, inviting a massive migration of media messages into your home. Despite the gargantuan quantity and diversity of entertainment at your fingertips, you are not satisfied by any of the options. This is due to both an increase in choice, which causes an increase in expectation and, thus, disappointment, as well as decrease in desire, since that which you once craved is now in your ownership. Some would complain that an increase in channels means there are fewer quality choices, but it is precisely because there are more quality choices that our desire decreases. A choice that would have been acceptable before is now rejected in search of something greater.

As for ownership, it is a poison to desire, causing it to wither like a severed vine. There are some situations where we can enjoy, with renewed passion, the things that we own. There is hope. Spain has a plan.

When we unsuspectingly encounter something we own, outside of our control, we are released from the bondage of ownership, free to enjoy it once again. When we find that our favorite movie is being shown on television, or our favorite song is playing on the radio, the shackles are shattered. Even though we could choose to enjoy the thing at any moment, it is only when we do not choose it that we can enjoy it. The exact cause for this exception is obscure, for now let’s just accept it as a gift.

So now that we know how to destroy desire, we also know how to cultivate it. We must preserve our desire; do not own the things you love. Borrow them, share them, rent them, but do not own them. Do not cage the beast of desire.