In the last episode I talked about missions; now I’m gonna talk about how they’re made.

A mission is just a JavaScript object, and so I originally just saved them in mission files like mission0.json, which looked something like this:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 |

{ "level": 1, "background": "space", "allyFaction": "empire", "enemyFaction": "rebel", "size": "normal", "speed": "normal", "entities": [ [{}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}], [{}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}], [{}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}], [{}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}], [{}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}], [{}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}], [{}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}], [{}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}], [{}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}] ] } |

Of course there would be more rows, but I don’t want to waste space. Also, the entity objects wouldn’t be empty, they’d contain a type, preset, and rotation:

|

1 |

{"type": "enemy", "preset": "bomber", "rotation": 90} |

Anyway, in order to test stuff, I was opening the mission files and manually changing stats and entering presets and types. It was annoying. I decided to create a tool that would make mission making easy. Enter the mission maker.

The Interface

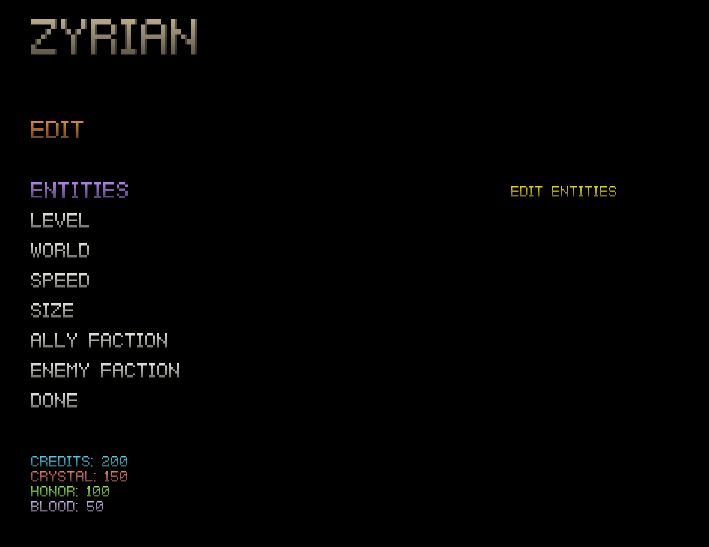

The mission maker is a graphical editor accessed through the game menu. It lets you edit all of the aspects of a mission…

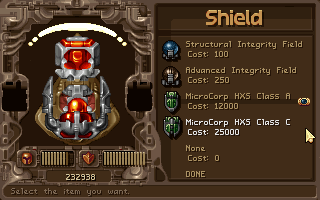

And customize the entities…

Patching the mission maker into the game menu was actually pretty tough.

Entities are loaded in rows and columns, so it makes sense to display them as a two-dimensional array (or grid), but the menu uses a tree structure. I ended up creating a new type of object called a grid that contains a two-dimensional array of nodes…

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 |

// A grid structure of nodes (2D array) var grid = function(rows, columns, parent) { this.cells = new Array(rows); // The 2D array of cell nodes for (var i = 0; i < rows; i++) { this.cells[i] = new Array(columns); } this.rows = rows; // The number of rows this.columns = columns; // The number of columns this.lastRowAdded = 0; // The row index of the last cell added to the grid this.lastColumnAdded = 0; // The column index of the last cell added to this.selectedCell = {}; // The currently selected cell this.chosenCell = null; // The currently chosen cell this.parent = parent || null // The parent node of the grid } |

Allowing the player to navigate the mission maker took a lot of time and some crappy programming, but I eventually got it working. Here were the hardest parts:

- Rolling over between the first and last rows

- Determining which nodes to show

- Rendering the entities

- Saving and loading a 2D array

- Empty nodes

- The waiting

After I’m done editing the mission, I just click the PRINT option, and it spits the text out to the console. Pretty neat.

Sharing

Shortly after conceiving of the mission maker, I realized that I could just leave it in the game and let players make their own missions. I suspect that this is what happens with strategy games like StarCraft and its campaign editor. After all, if you’re going to make an editor, why not let player use it?

So I made the mission maker with players in mind, but I had no idea how I was going to have them share their missions. Here were my options:

- Print the mission object to the screen and have players copy it to a text file

- Create links that players send to one another

- Host a page where players post missions

The third option definitely the best, since it could allow players to discuss, rate, tag, name, categorize, and search for missions. However, it would also be quite a bit of work. My focus was (and is) to finish the game, so I went with the second option.

By incorporating a JavaScript version of PHP’s GET function, I can retrieve text from the URL and pass it into a variable. This means players can load missions by clicking a link, and they can share them just as easily. But there’s a problem…

Encoding

Missions have hundreds of entities, and each entity has a type, preset, and rotation. This means that our mission text can be thousands of characters long! Not only is this annoying, it also can cause problems in some browsers.

To get around this, I developed an encoding system that compresses the mission object into a string of text. It’s super simple.

For the mission stats, it just keeps the first letter of the factions, speed, and size. For the entities, it does the same for the type and preset, then it changes the rotation into a single digit. Then it looks for repeating entities and records the count (empty spaces are recorded as dashes).

So an entity changes from this…

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 |

{ "level": 1, "background": "space", "allyFaction": "empire", "enemyFaction": "rebel", "size": "normal", "speed": "normal", "entities": [ [{"type": "enemy", "preset": "bomber", "rotation": 90}, {"type": "enemy", "preset": "bomber", "rotation": 90}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {}] ] } |

Into this…

|

1 |

"1sernneb12---7" |

I was super proud when I got this to work. But then I had to write a decoder that turns it back into a mission object. Ugh.

Rotation

You may have noticed that I’ve mentioned entity rotation a few times, and I’m finally going to explain it.

An entity’s rotation determines what angle it’s facing and, for vessels, what side of the screen it enters from. For turrets and obstacles, rotation merely spins the entity. Drops can’t be rotated at all.

Note: I did end up changing obstacle rotation so that some of them rotate randomly once they are spawned, so they can’t be rotated in the editor.

Rotation can only be done in increments of 90 degrees, so an enemy vessel can enter the screen from straight on, the left, the right, or from behind. And just as if the entity was entering from above, the vessel’s position in the row determines where on that side of the screen it will spawn.

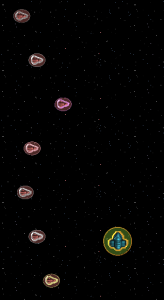

So, for example, a row of vessels like this…

Will enter like this…

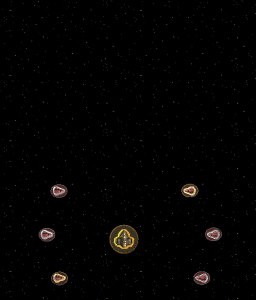

And this kind of row…

Will look like so…

I don’t know if this is the best way to handle rotation, but it’s the only way I could think to do it at the time.

There’s much more I want to do with the mission maker, and there are many decisions to be made. Such as:

- Where is the mission maker located in the menu?

- Does the player use their current save in a custom mission?

- Can players keep reward they collect in a custom mission?

- What are the default custom mission settings?

- How do I handle sprite size in the mission maker?

- Can the player put drops into a mission?

- Shouldn’t large entities take up more than one space in the mission maker?

- Won’t large entities overlap larger missions?

- Should the player be able to customize entities in the mission maker?

- Could we have entities enter from all sides at the same time?

I’ll probably do another episode on the mission maker if I end up making significant changes to it.

Stay tuned!